Microbiota from obese donors for the treatment of cancer-related cachexia?

Feared by cancer patients, cachexia is difficult to treat despite nutritional support. What if gut flora from overweight or obese donors could reverse the trend?

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

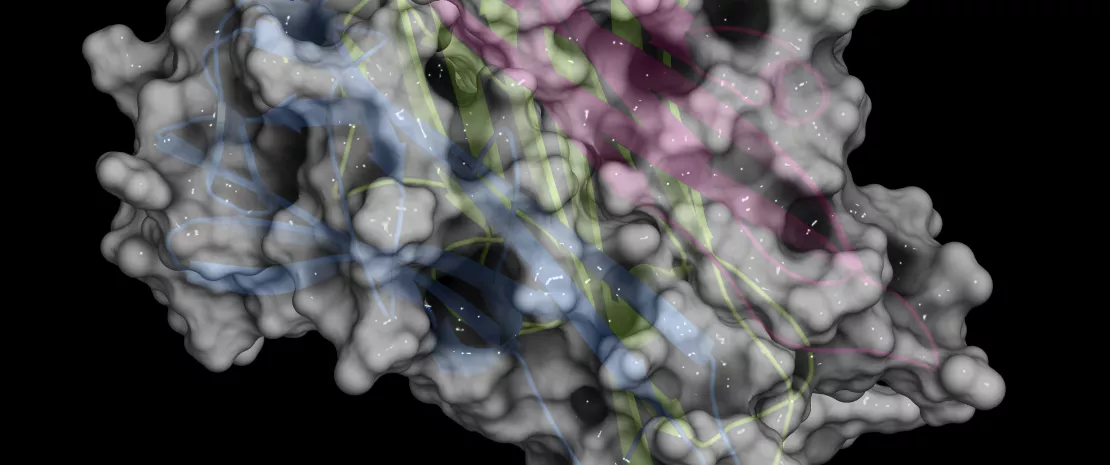

Cachexia is defined as a multifactorial syndrome characterized by an ongoing loss of muscle mass that cannot be reversed by conventional nutritional support. The syndrome leads to progressive functional impairment, reduced tolerance to anticancer treatments and shorter survival times. Gastroesophageal cancer (GEC) patients are particularly at risk as their mechanical and digestive problems lead to loss of appetite and early satiety. Gut microbiota appears to play a crucial role in regulating certain aspects of cancer cachexia, such as satiety, appetite, host metabolism, systemic inflammation or modulation of the response to certain anticancer drugs. However, this role is impaired by cancer and most anticancer treatments that alter the intestinal barrier. Hence the idea to study the effects of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) on cachexia in GEC patients.

Study parameters: satiety, survival, and gut microbiota

This double-blind, randomized, controlled study was conducted on 24 cachectic patients with inoperable metastatic GEC undergoing palliative chemotherapy. These patients received allogenic FMT (treatment group; healthy overweight or obese donor) or autologous FMT (control group; donor = patient). The primary research objective was to evaluate the effect of FMT on satiety. Other characteristics of cachexia were also monitored, as well as the effectiveness of chemotherapy and survival. Lastly, exploratory analyses measured the effect of FMT on the composition of the gut microbiota.

No impact on satiety, but beneficial effect on disease progression

Contrary to expectations, allogenic FMT from a healthy obese donor did not improve the recipient's satiety or cachexia before chemotherapy. It nevertheless appears to have had a beneficial effect on disease progression: when compared to the control group, the 12 patients in the treatment group had a better disease control rate (based on RECIST criteria) at 12 weeks, and longer overall (365 vs. 227 days) and progression-free survival (204 vs. 93 days). Three patients in the control group and none in the treatment group died of cancer before the end of the study. The patients' fecal microbiota also changed after allogenic FMT, indicating proper engraftment of the donor microbiota despite chemotherapy. The researchers were unable to identify specific gut bacterial species associated with chemotherapy outcomes in the treatment group. FMT studies on a larger scale will be needed. Ultimately, the hope is for personalized treatments, via the administration of prebiotics and probiotics specifically adapted to a patient's microbiota to improve the effectiveness of anticancer drugs.