The male genital microbiota impact on women’s health

By Prof Jean-Marc Bohbot

Director, The Fournier Institute, Paris, France

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Author

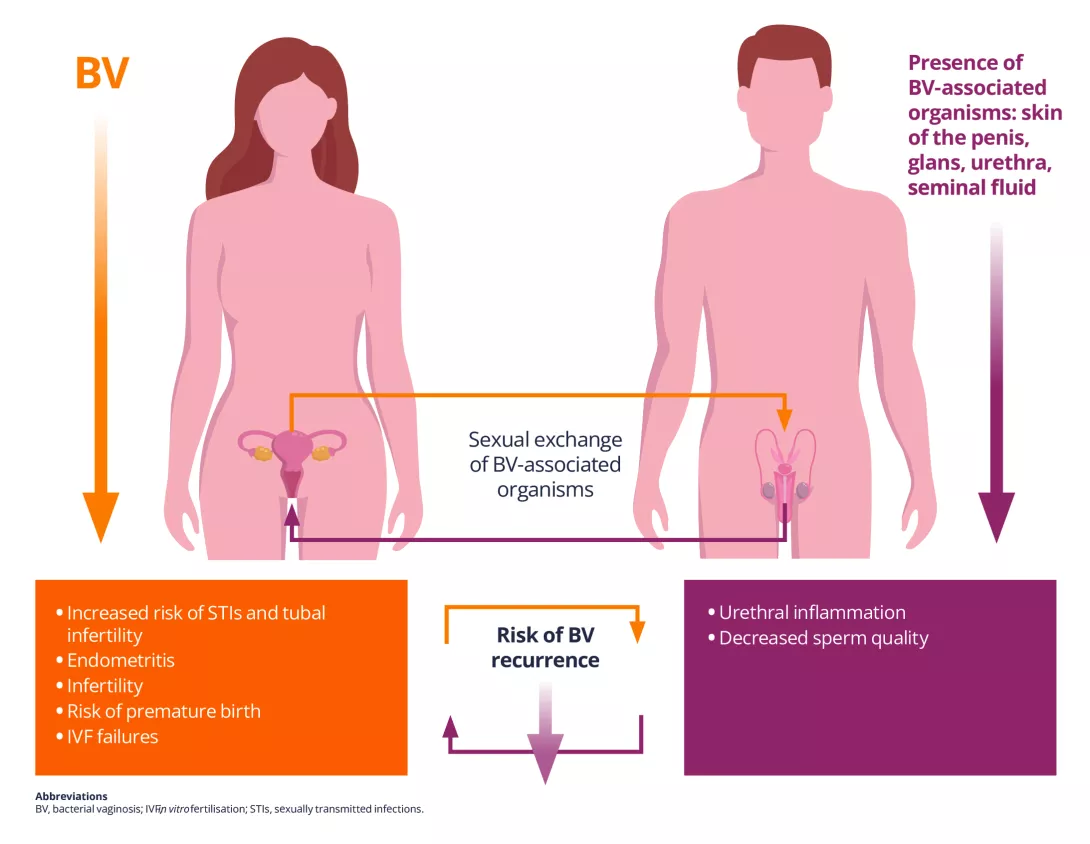

Talk about vaginal infections, fertility, or pregnancy complications often focuses solely on women. But there is another important player: the male urogenital tact (MUGT). The wide variety of microbes in the MUGT can significantly affect female reproductive and vaginal health (Figure 1). Understanding these influences may improve outcomes for women, especially those with persistent vaginal infections, fertility challenges, and pregnancy complications.

Figure 1. Consequences of exchanges of bacteria associated with vaginosis during sexual contact between males and female

What do we know about the male genital microbiota?

The MUGT includes several distinct microbial environments: the skin of the penis, the urethra, semen, and the urinary tract. Each has a unique bacterial community, influenced by factors like circumcision, sexual practices, hygiene, and lifestyle.

The skin of the penis harbours bacteria similar to those found on other cutaneous (skin) surfaces — mainly Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus genera1, 2. In uncircumcised men, the area under the foreskin (the balanopreputial sulcus) is dominated by anaerobic bacteria such as Anaerococcus, Peptoniphilus, Finegoldia, and Prevotella, some of which are also found in women with bacterial vaginosis (BV)1, 2. Circumcision significantly reduces these anaerobes, which may explain why women with circumcised partners have a lower risk of BV2.

Sampling the urethra directly is painful, so most studies use the first-void urine as a proxy to study urethral microbiota. This fluid contains a mix of bacteria like Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Sneathia, Veillonella, Corynebacteria, and Prevotella3. Interestingly, some of these are linked to BV (e.g. Gardnerella vaginalis) and aerobic vaginitis (S. agalactiae)4.

Semen is not just sperm — it also includes fluids from the prostate and seminal glands. Studies show that a Lactobacillus-dominated seminal microbiota is linked to better sperm quality, while other bacteria (e.g. Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma, Prevotella, and Klebsiella pneumoniae) are associated with lower fertility5.

The male urinary microbiota is less studied, but lower levels of Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Pseudomonas, and Enterococcus genera have been found in men with abnormal sperm concentration compared with men with normal sperm concentration6. Men with abnormal sperm motility may have high levels of Dialister micraerophilus bacteria, which contribute to a proinflammatory sperm microenvironment6.

MUGT microbiota vary with circumcision status, sexual practices, and the composition of the female partner’s vaginal microbiota7.

Interestingly, the urethral microbiota of homosexual men does not seem to be modified by the type of sexual intercourse (oral or anal)8. Bacterial exchanges between partners during sexual contact are the rule; why these exchanges lead to vaginal dysbiosis in some cases and not others is unclear.

Seminal microbiota are also influenced by several physiological functions (age, hormonal changes) and lifestyle or epigenetic factors

(tobacco, alcohol, obesity, high-fat diet, exposure to toxins)5. These modifiable factors are potential targets for intervention.

How does the MUGT impact female health?

The transmission of microorganisms responsible for bacterial and viral sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV and herpes simplex virus infection during sexual contact is the most obvious consequence of how the MUGT impacts female health. The female complications of bacterial STIs (gonorrhoea, infections by Chlamydia trachomatis or M. genitalium) are well known (inflammation and infection of the upper genital tract, risk of tubal infertility).

Many studies have shown that the epidemiological profile of women with BV is comparable to that of women with STIs, suggesting possible sexual transmission of the bacteria involved in BV. The presence of BV-associated bacteria in the foreskin and urethra of partners of women with BV and a concordance of vaginal and male urethral bacterial strains support the sharing of these strains or sexual transmission of BV.

Treating the male partner with oral antibiotics (metronidazole) has had very limited impact on recurrence rates in women with recurrent

BV, although combining metronidazole with a topical antibiotic applied to penile skin in partners of women with BV may reduce the risk of recurrence9.

The impact of the MUGT on uterovaginal health is not limited to passive bacterial transfer. Seminal fluid contains proinflammatory substances (such as prostaglandins) that can interfere with immune responses and inflammation within the female genital tract10.

KEY POINTS

- The male genital microbiota plays an influential but underrecognised role in female reproductive health, particularly in recurrent genital infections and fertility challenges.

- Routine STI screening may miss important bacteria that are not traditionally classified as pathogens but disrupt the female genital microbiota.

- Male-partner treatment for recurrent BV may need to go beyond oral antibiotics, incorporating topical therapies and addressing shared risk factors.

CONCLUSION

The male urogenital microbiota matters — not just for men’s health, but for women’s too. While research is still evolving, it is clear that male partner dynamics, lifestyle, and microbial exchange influence female urogenital health. The evidence increasingly supports a more holistic, couple-based approach to managing reproductive concerns, by incorporating male partner care into routine sexual and reproductive health strategies to improve outcomes for both partners, especially in cases of persistent or recurrent vaginal infections. Encouraging healthier habits in men — including quitting smoking or improving the diet — might improve semen microbial health and reduce the risk of negative outcomes for their female partners.