Can we target microbiota in the management of children with functional abdominal pain disorders?

By Iulia Florentina Tincu, Roxana Elena Matran, Cristina Adriana Becheanu

Carol Davila University of Medecine and Pharmacy, Romania

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

The dysbiotic gut in functional abdominal pain disorders in children

Functional abdominal pain disorders (FAPDs), also referred to as functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), represent the one of the main etiologies of chronic abdominal pain in the pediatric population that involve interplay among regulatory factors in the enteric and central nervous systems 1. The ongoing classification system, ROME IV, distinguishes several pain-predominant FGIDs based on their recognizable patterns of symptoms, such as functional dyspepsia (FD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), abdominal migraine, and FAP-not otherwise specified (FAP-NOS) 2. During the past two decades numerous studies researched possible causes and underlying mechanisms of appearance, but the clear pathophysiology is yet to be revealed, despite pediatric neurogastroenterology findings in terms of intestinal motility, signaling molecules, changes in microbiota or epigenetic mechanisms 3. Gut microbiota modifications, known as a dysbiotic gut, may play a role in functional abdominal pain disorders through gut immunity and integrity alteration 4, 5. Several studies have reported a lower level of microbial diversity in patients with functional abdominal pain disorders 6, 7 and species such as Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria are heavily altered 8. Thus, a growing body of clinical data have been gathered around using probiotics in functional disorders’ management, although study data are lacking on children 9.

Research insights

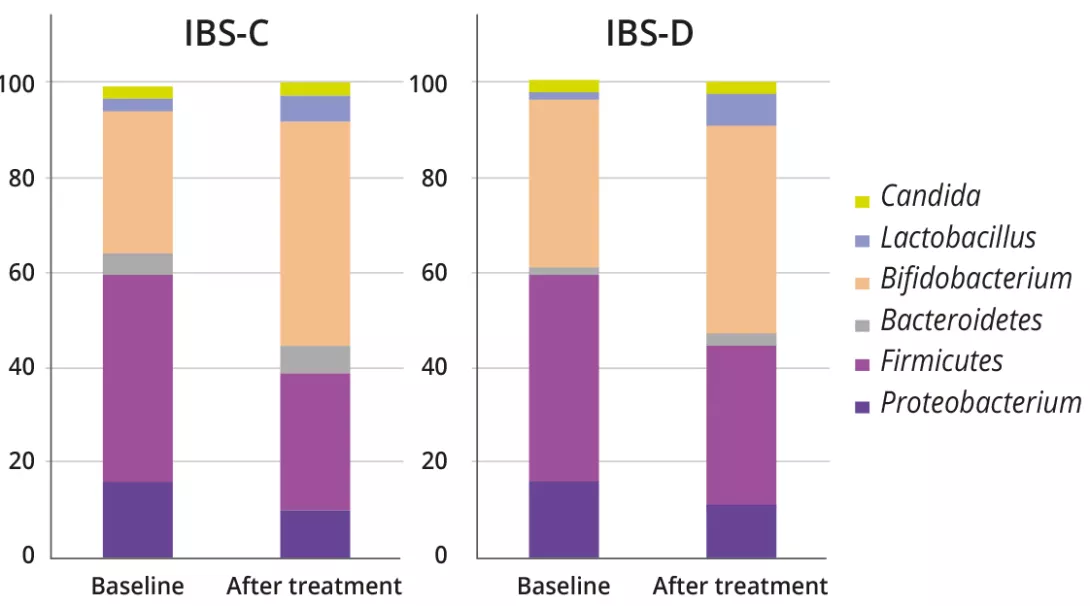

The analysis of microbiota in 18 patients with FGIDs provided data about intestinal dysbiosis at the moment of the diagnosis and its changes over a period of three months of treatment with specific strains of probiotics and prebiotics (figure 1).

Individuals. Age 4-14 years and diagnosed with functional abdominal pain disorders (functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome) according to ROME IV criteria.

Intervention. Six bacterial strains (Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011, Lactobacillus casei R0215, Bifidobacterium lactis BI-04, Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14, Bifidobacterium longum BB536, Lactobacillus plantarum R1012) and 210 mg of fructo-oligosaccharides-inulin. One capsule was administered orally, daily, for 12 weeks, and the medication was provided by the healthcare practitioners.

Clinical outcome. The patients were scored for severity of abdominal discomfort, dyspepsia, flatulence, and epigastric pain on a ten-point ordinate (numerical rating) scale.

Fecal samples were collected from participants before and after treatment using a special laboratory kit with two sterile containers, which were then brought to the laboratory in conditions depending on the time spent from collection to laboratory delivery: if the interval was less than 24 hours, both containers were stored and transported in cooled conditions at 4 °C; if the period between stool elimination and laboratory delivery was more than 24 hours, one container was stored in a frozen condition at – 80 °C until analysis, and the other one was cooled at 4 °C. Stool samples were analyzed using the test Colonic dysbiosis-basic profile (SBY 1) performed by Synlab-Germany. Microbiota composition was expressed as number of colony forming units (CFU) for various aerobic/anaerobic bacterial and fungal species. The analysis provided data on fecal pH, IgA in μg/mL (normal ranges 510–2,040 μg/mL), lactoferine μg/ mL (normal ranges < 7.2), calprotectin in mg/kg (normal ranges < 50.0 negative, 50–99 intermediary, > 100 positive).

In the fecal microbial analysis, there was an increasing proportion of bacterial genera associated with health benefits (e.g., Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus), for both IBS-C and IBS-D (IBS-C: 31.1 ± 16.7% vs. 47.7 ± 13.5%, p = 0.01; IBS-D: 35.8 ± 16.2% vs. 44.1 ± 15.1%, p = 0.01). On the other hand, genera of harmful bacteria, including Escherichia, Clostridium, and Klebsiella were proven to decrease after treatment (21.3 ± 16.9% vs. 16.3 ± 9.6%, p = 0.02).

No particularities were found in children with FD. At baseline, before any symbiotic intervention, Bifidobacterium profiles were significantly different between IBS-C and IBS-D (87.14 ± 23.19 vs. 71.37 ± 12.24; p = 0.02), with lower counts in IBS-D. The symbiotic administration had a significant effect on bacterial profiles from baseline to the end of treatment in both IBS-C and IBS-D groups (Table 1).

Practical consequences

The clinical symptoms in study population were more diminished after treatment, with statistical significance, suggesting that influencing gut dysbiosis might also reduce patients’ burden and improve clinical scores.

Overall, 14 (78%) patients reported treatment success (defined as no pain). The proportion of patients with adequate symptom relief was higher in the IBS-D than in the IBS-C group; however, the difference was not statistically significant (74.4% vs. 61.9%, p = 0.230). In both IBS-C and IBS-D groups, scores on the Bristol scale improved significantly after intervention (baseline vs. after treatment; 2.8 ± 0.6 vs. 3.9 ± 0.9, p = 0.03, 6.1 ± 0.9 vs. 4.1 ± 1.0, P = 0.01, respectively). Abdominal distension and flatulence were significantly improved in both IBS-C and IBS-D groups (IBS-C: 6.5 ± 2.8 vs. 3.7 ± 1.8, p = 0.01; IBS-D: 5.9 ± 2.2 vs. 2.9 ± 1.8, p = 0.01).

- The exploration of human microbiome revealed over time that dysbiosis has a substantial role in pathogenesis of functional abdominal pain disorders, although specific profiles as early biomarkers are still far from current practical use.

- There is a real need for future unitary studies in terms of microbiota-modifying interventions for a broader landscape of pediatric disorders.

- We can conclude that a novel perspective in the growing field of microbiota modifying therapies in children with FGIDs may offer valuable insights of disease mechanisms so personalized therapeutic strategies might improve patients’ symptoms.

Conclusion

Microbiota targeted intervention might result in significant changes in the gastrointestinal dysbiosis and this finding is related to gastrointestinal symptoms relief in patients with functional abdominal pain disorders.

- Royle JT, Hamel-Lambert J. Biopsychosocial issues in functional abdominal pain. Pediatr Ann 2001; 30: 32-40.

- Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M. Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterology 2016: S0016-5085.

- Oświęcimska J, Szymlak A, Roczniak W, Girczys-Połedniok K, Kwiecień J. New insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Adv Med Sci 2017; 62: 17-30.

- Chong PP, Chin VK, Looi CY, Wong WF, Madhavan P, Yong VC. The Microbiome and Irritable Bowel Syndrome - A Review on the Pathophysiology, Current Research and Future Therapy. Front Microbiol 2019; 10: 1136. Erratum in: Front Microbiol 2019; 10: 1870.

- Pantazi AC, Mihai CM, Lupu A, et al. Gut Microbiota Profile and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Infants: A Longitudinal Study. Nutrients 2025; 17: 701.

- Carroll IM, Ringel-Kulka T, Keku TO, et al. Molecular analysis of the luminal- and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011; 301: G799-807.

- Rosa D, Zablah RA, Vazquez-Frias R. Unraveling the complexity of Disorders of the Gut-Brain Interaction: the gut microbiota connection in children. Front Pediatr 2024; 11: 1283389.

- Bellini M, Gambaccini D, Stasi C, Urbano MT, Marchi S, Usai-Satta P. Irritable bowel syndrome: a disease still searching for pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 8807-20.

- Klem F, Wadhwa A, Prokop LJ, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Irritable Bowel Syndrome After Infectious Enteritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017; 152: 1042-54.