When drugs meet microbes: a bidirectional dialogue with therapeutic implications

By Prof. Emmanuel Montassier

Emergency Department, CHU Nantes; Inserm, Center for Research in Transplantation and Translational Immunology, UMR 1064, Nantes Université, Nantes, France

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Bidirectional interactions between oral drugs and the gut microbiome are increasingly seen as crucial to drug efficacy, safety, and tolerability. While antibiotics are known to disrupt microbial communities, about 24% of non-antibiotic drugs also inhibit at least one commensal species. Additionally, 10–15% of oral drugs are transformed by gut microbes in vivo, affecting their effectiveness or toxicity. Common medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPI), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), metformin, and statins can alter microbiota composition and function, influencing host metabolism and immunity. Despite these findings, the microbiome is often overlooked in prescribing and in drug development. This review summarizes key clinical and mechanistic insights, highlights notable drug–microbiota interaction, and explores emerging strategies to enhance outcomes. Integrating pharmacomicrobiomics into clinical care may reduce adverse effects and support precision medicine.

The gut microbiota acts as a metabolic organ, supporting digestion, immunity, and homeostasis 1. Its interaction with drugs, however, is bidirectional: medications can disrupt microbial balance, while microbes can alter drug activity. This makes the microbiome a significant yet often overlooked factor in adverse drug reaction (ADR) risk 2, 3. Gut microbial enzymes can transform drugs into more toxic forms, increasing tissue exposure and harmful effects. Growing evidence highlights microbial variability as a key driver of individual differences in drug response and ADRs 2, 4. Integrating pharmacomicrobiomics into risk assessment alongside genetics and clinical data could help predict susceptibility to drug-related harm and guide personalized prevention strategies.

Drug-induced microbiota disruption: antibiotics and beyond

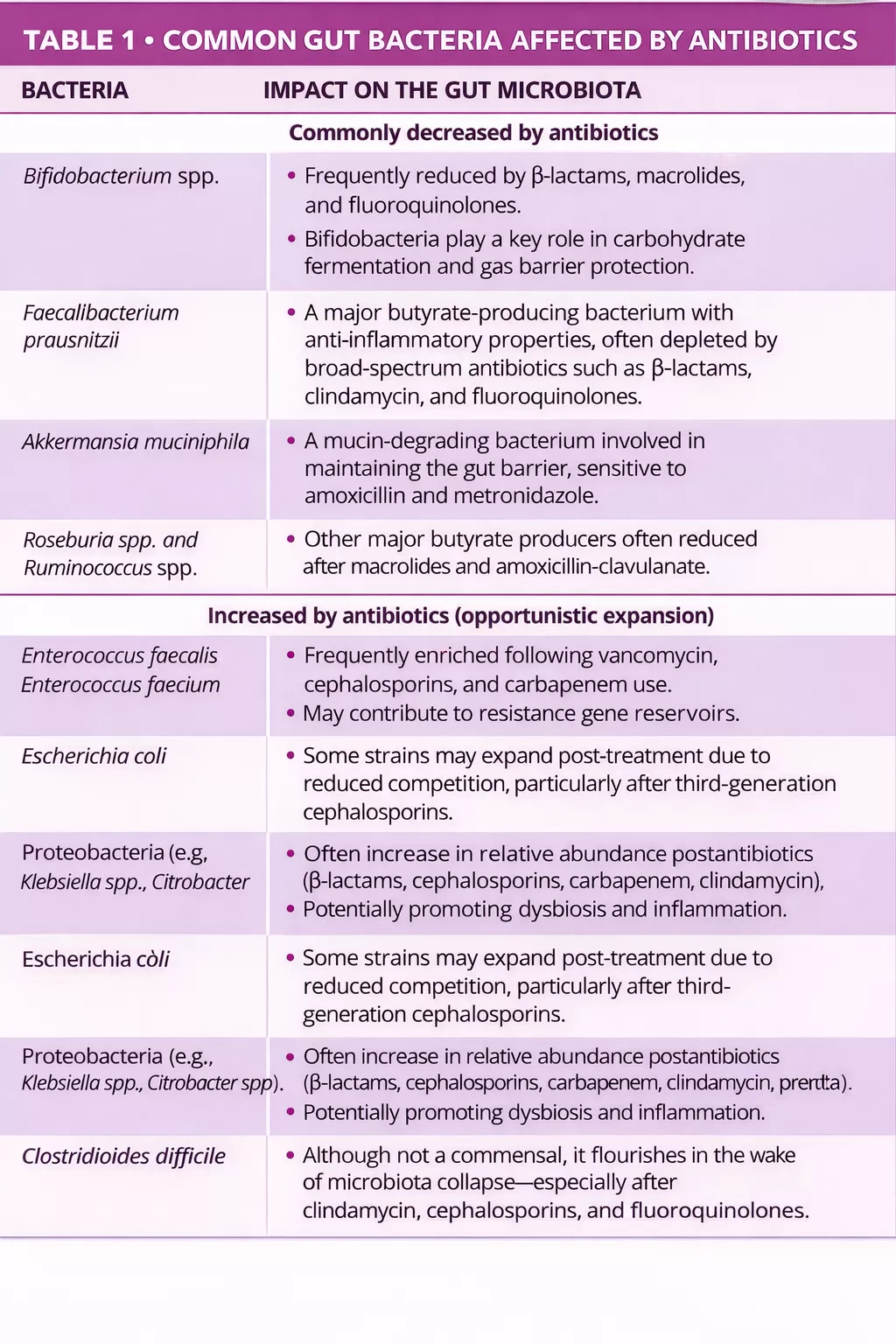

Antibiotics are well known to disrupt the gut microbiota by reducing diversity, altering composition, and promoting resistant strains (table 1) 5, 6. Van Zyl et al. found that antibiotics especially quinolones and β-lactams consistently disrupt microbial communities across body sites, with combination regimens causing prolonged dysbiosis and increased pathogenic burden 5. Similarly, Maier et al. showed that different antibiotic classes have distinct effects on gut bacteria, with macrolides and tetracyclines causing sustained losses in anaerobes, and drugs like amoxicillin and ceftriaxone shifting populations toward Proteobacteria. Despite individual variability, a common trend emerged: depletion of obligate anaerobes (e.g., Firmicutes) and enrichment of facultative and potentially pathogenic microorganisms 6.

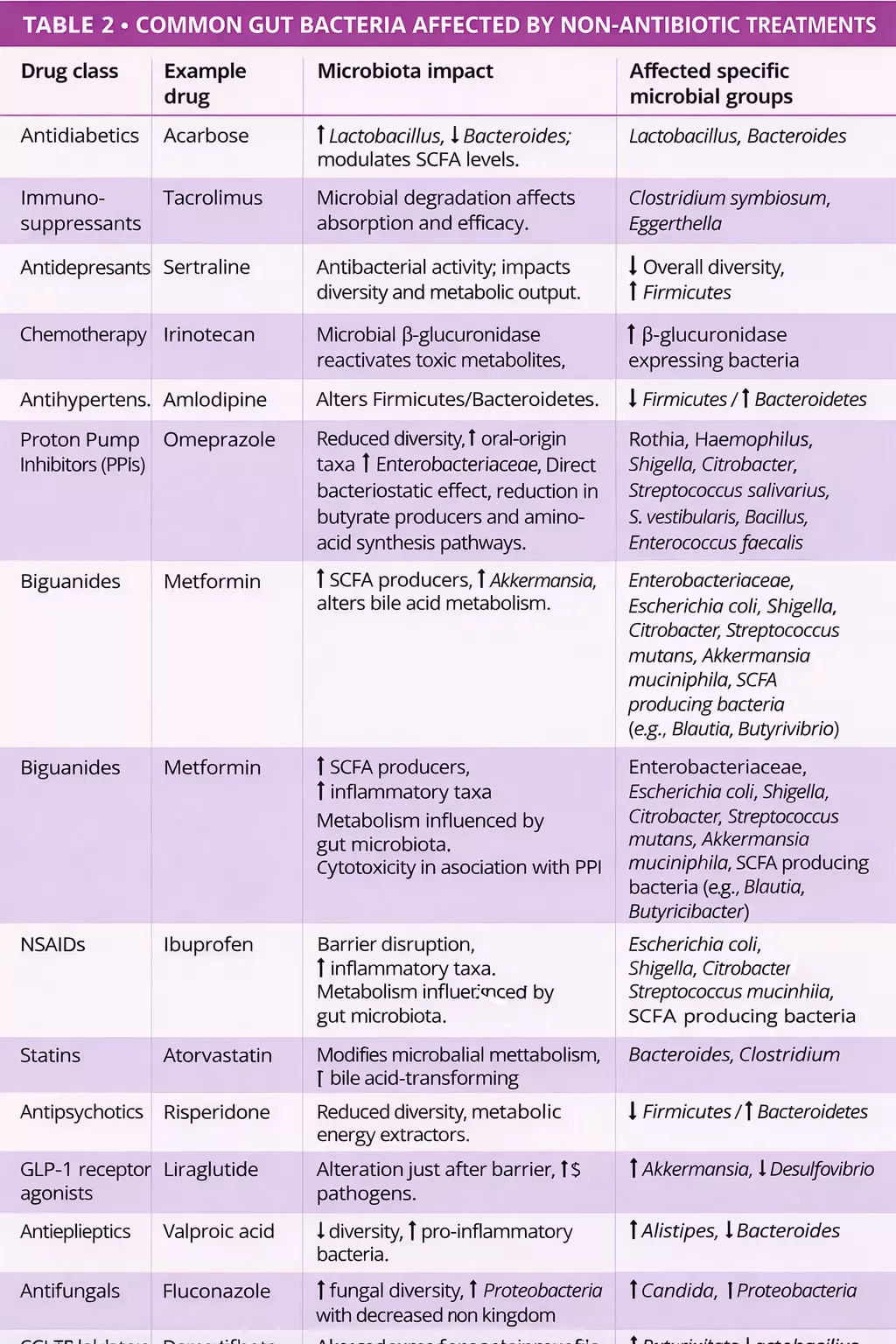

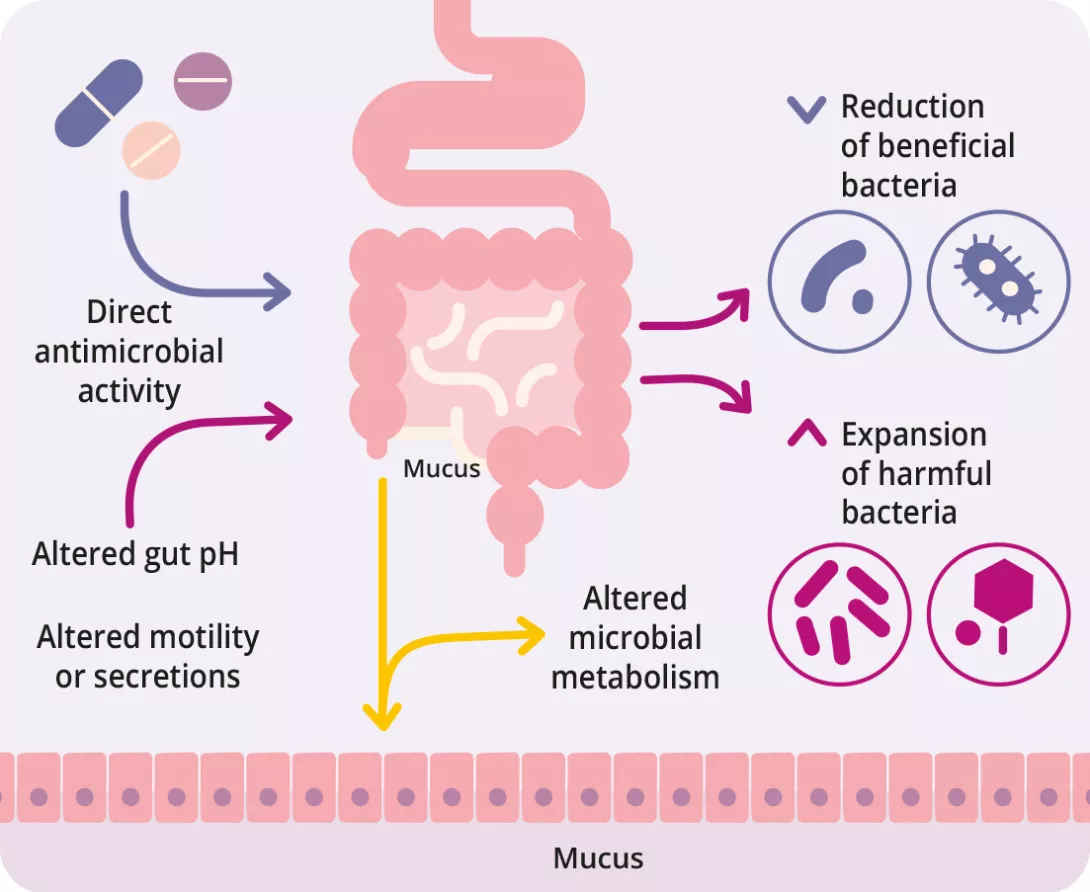

Beyond antibiotics, many non-antibiotic drugs including PPIs, metformin, NSAIDs, antipsychotics, and statins also alter the gut microbiota (figure 1, table 2) 7, 8. Drugs influence the gut microbiota through various mechanisms direct antimicrobial action, altered pH, bile acid modulation, intestinal motility changes, and mucus secretion 9.

Gut microbiota modifies drugs metabolism

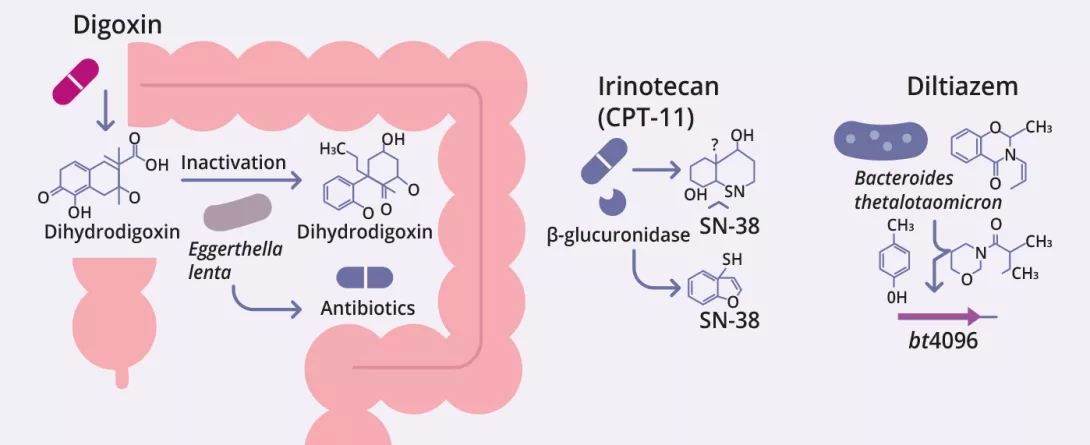

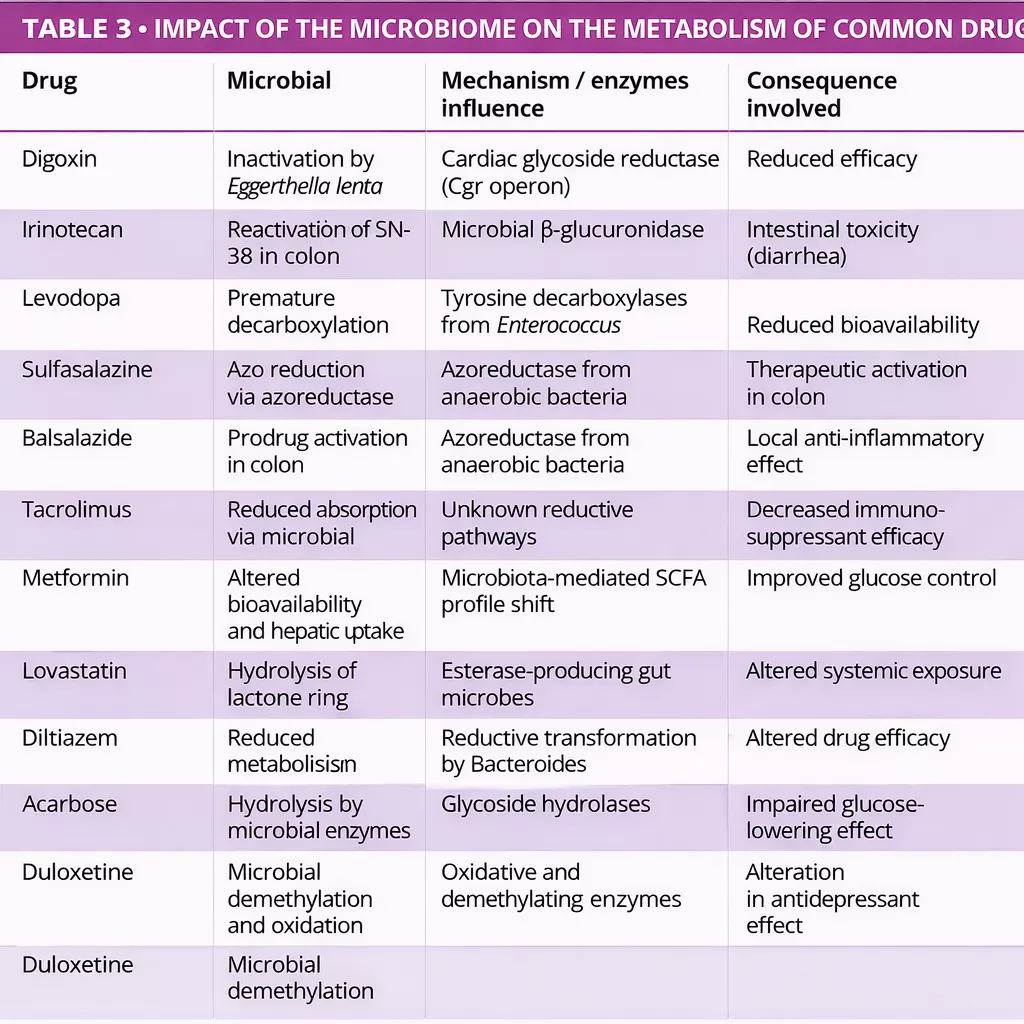

The gut microbiota can biotransform therapeutic drugs, altering their activity, efficacy, and toxicity (figure 2, table 3) 12-14. Zimmermann et al. mapped microbial metabolism by screening 271 oral drugs against 76 gut bacterial strains, finding that 176 were metabolized by at least one strain. Notably, Bacteroides dorei and B. uniformis metabolized nearly 100 drugs. Over 40 microbial enzymes were identified,

mediating a wide range of reactions including reduction, hydrolysis, decarboxylation, dealkylation, and demethylation 12.

Javdan et al. developed a personalized platform (MDM-Screen) to assess microbial drug metabolism using ex vivo microbiota from individual donors. Screening 575 drugs, they found that 13% were metabolized by gut microbes, including many previously unrecognized interactions. These transformations such as hydrolysis, reduction, and deacetylation can activate, inactivate, or increase drug toxicity. The study also revealed significant inter-individual variability and identified key microbial genes (e.g., uridine phosphorylase, β-glucuronidase) linked to specific metabolic pathways 15.

The efficacy of some drugs may depend more on the microbiota composition than on the host genetics.

Clinical consequences: toward personalized medicine

Microbiota-drug interactions have major clinical implications, as individual differences in gut microbiota may explain variability in drug response and side effects. Importantly, it is not just microbiota composition but also its functional stability that influences treatment outcomes.

In advanced melanoma, patients responding well to anti-PD-1 therapy showed stable microbial functions and CD8+ T cells reactive to bacterial peptides from Lachnospiraceae, which mimic tumor antigens highlighting microbial functionality as a potential prognostic marker and therapeutic adjunct in cancer immunotherapy 16.

These insights underscore the need to integrate both human and microbial genomics into pharmacological assessments. In drug development, simulating microbiota–drug interactions in silico has become key. Dodd and Cane proposed a detailed framework combining in vitro systems (e.g., strain libraries, stool-derived communities), genetic tools (gain/loss-offunction assays), and metagenomics to identify microbial genes involved in drug metabolism. Gnotobiotic mouse models further help disentangle microbial from host effects on pharmacokinetics.

As this field advances, microbiota-informed prescribing is emerging as a way to tailor treatments and reduce adverse effects. In the future, pharmacomicrobiomics could guide drug choices and dosages based on microbial biomarkers, enabling truly personalized medicine 17.

Personalizing treatment could one day require a microbiota fingerprint.

Preserving and restoring the microbiota: a therapeutic frontier

Protecting the gut microbiota during drug therapy is a promising strategy to reduce ADRs and preserve efficacy. While probiotics and prebiotics show some benefit against drug-induced dysbiosis, their effectiveness varies. Targeted probiotics tailored to specific drug effects, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), particularly for recurrent C. difficile infection, offer more reliable options.

Precision tools such as microbial enzyme inhibitors (e.g., β-glucuronidase blockers for irinotecan toxicity), bioengineered probiotics,

microbiota-sparing drug designs, and diet-based interventions are under investigation. Clinical trials are exploring synbiotics customized to drug regimens to improve outcomes with minimal microbiota disruption. Postbiotics like butyrate are also being evaluated for anti-inflammatory and gut barrier-supporting effects.

Integrating microbiota-targeted strategies into pharmacology will require advanced tools multi-omics, machine learning, and systems microbiome modeling to predict and manage microbiota–drug interactions effectively.

Manipulating the gut microbiota may enhance treatment success and reduce complications.

Conclusion

Microbiota–drug interactions are an emerging and often overlooked aspect of medicine with major implications for treatment outcomes. Integrating these insights into clinical practice is key to developing safer, more precise, and microbiota-aware therapies. As evidence grows, new opportunities arise to modulate the microbiome to boost efficacy, reduce toxicity, and rescue drug responses.

Innovative approaches such as live biotherapeutics, engineered microbes, and microbiota-derived metabolites (“pharmabiotics”) are reshaping pharmacotherapy. Although regulatory interest is increasing, standardized clinical protocols are still developing. In the near future, microbiome engineering could become a routine component of personalized, systems-based medical care.

- Valdes AM, Walter J, Segal E, Spector TD. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ 2018; 361: k2179.

- Zhao Q, Chen Y, Huang W, Zhou H, Zhang W. Drug-microbiota interactions: an emerging priority for precision medicine. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023; 8: 386.

- Wallace BD, Wang H, Lane KT, et al. Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science 2010; 330: 831-5.

- Bolte LA, Björk JR, Gacesa R, Weersma RK. Pharmacomicrobiomics: The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Immunomodulation and Cancer Therapy. Gastroenterology 2025 Online publication ahead of print.

- Nel Van Zyl K, Matukane SR, Hamman BL, Whitelaw AC, Newton-Foot M. Effect of antibiotics on the human microbiome: a systematic review. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2022; 59: 106502.

- Maier L, Goemans CV, Wirbel J, et al. Unravelling the collateral damage of antibiotics on gut bacteria. Nature 2021; 599: 120-4.

- Vich Vila A, Collij V, Sanna S, et al. Impact of commonly used drugs on the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 362.

- Macke L, Schulz C, Koletzko L, Malfertheiner P. Systematic review: the effects of proton pump inhibitors on the microbiome of the digestive tract-evidence from next-generation sequencing studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020; 51: 505-26.

- Le Bastard Q, Berthelot L, Soulillou JP, Montassier E. Impact of non-antibiotic drugs on the human intestinal microbiome. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2021; 21: 911-24.

- Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 2018; 555: 623-8.

- Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Fu J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut 2020; 69: 1510-9.

- Zimmermann M, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Wegmann R, Goodman AL. Mapping human microbiome drug metabolism by gut bacteria and their genes. Nature 2019; 570: 462-7. •

- Haiser HJ, Gootenberg DB, Chatman K, Sirasani G, Balskus EP, Turnbaugh PJ. Predicting and manipulating cardiac drug inactivation by the human gut bacterium Eggerthella lenta. Science 2013; 341: 295-8.

- Takasuna K, Hagiwara T, Hirohashi M, et al. Involvement of beta-glucuronidase in intestinal microflora in the intestinal toxicity of the antitumor camptothecin derivative irinotecan hydrochloride (CPT-11) in rats. Cancer Res 1996; 56: 3752-7.

- Javdan B, Lopez JG, Chankhamjon P, et al. Personalized mapping of drug metabolism by the human gut microbiome. Cell 2020; 181: 1661-79.e22.

- Macandog ADG, Catozzi C, Capone M, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the gut microbiota during anti-PD-1 therapy reveals stable microbial features of response in melanoma patients. Cell Host Microbe 2024; 32: 2004-18.e9.

- Dodd D, Cann I. Tutorial: Microbiome studies in drug metabolism. Clin Transl Sci 2022; 15: 2812-37.