Gut–mind–pelvic axis: new insights from microbiome science

What if the microbes in a woman’s gut and vagina could predict her stress, sexual well-being, or recovery from cancer? A new study reveals the microbiome isn’t just a passenger, it may be an unseen driver of quality of life in endometrial disease.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

Doctors treating endometrial cancer often focus on surgery, hormones, and tumor grade. But what if the microbes living in a patient’s body are quietly shaping how she feels, her stress levels, digestion, and even sexual interest? A new study from researchers at the University of Oklahoma turns that question into data 1. They followed 140 women scheduled for hysterectomy, some with endometrial cancer (EC, n=47), others with benign gynecologic conditions such as fibroids or endometriosis (n=93).

Before surgery, each woman completed validated surveys assessing mental and physical health, GI symptoms, stress, sexual function, and vaginal comfort. At the same time, scientists collected vaginal and rectal swabs for microbiome sequencing. The goal: connect quality-of-life metrics to microbial fingerprints across two key body sites.

The microbial paradox of endometrial cancer

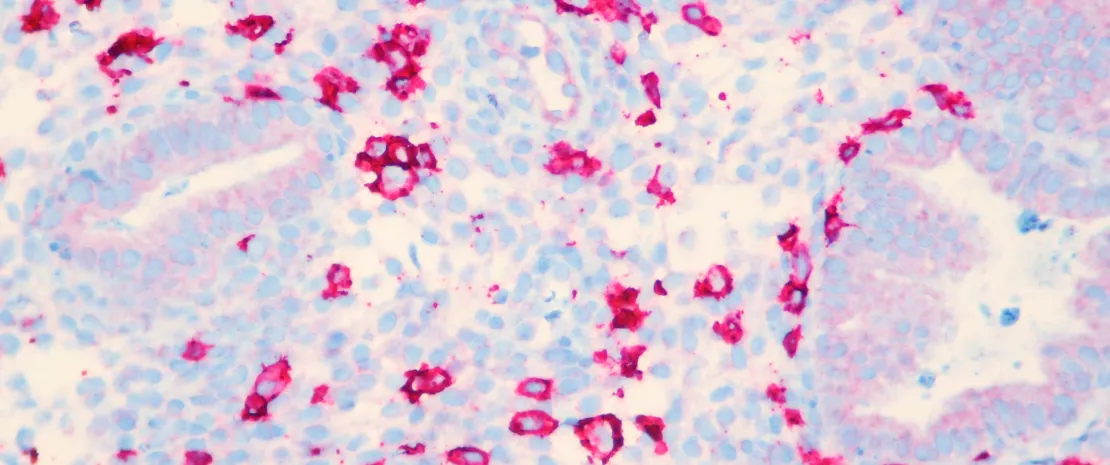

Here’s where things got surprising. In most healthy women, low vaginal diversity, dominated by protective Lactobacillus crispatus species, is considered a sign of balance. But in this study, endometrial cancer patients showed the opposite pattern: they had higher

(sidenote:

Vaginal microbial diversity

Refers to the variety and balance of bacterial species living in the vagina. Changes in this diversity can influence symptoms like dryness, irritation, and infection risk.

)

, and the more diverse their microbiome, the worse their vaginal dryness and irritation. Even more unexpected,

(sidenote:

Lactobacillus iners

A less protective vaginal bacterium that produces only L-lactic acid, often associated with microbial imbalances and vulnerability to opportunistic infections

)

, often thought of as not very “friendly”, was enriched in women reporting worse symptoms, alongside Lactobacillus gasseri, and Streptococcus agalactiae, a rather “friendly” vaginal bacteria. In short, microbes that normally spell health appeared to coincide with discomfort in this cancer population, suggesting that the rules of vaginal ecology may shift under oncologic conditions.

The gut–mind–pelvic connection

The rectal microbiome also told an intriguing story. In women with EC, certain gut bacteria, especially (sidenote: Gastranaerophilales An order of gut bacteria that, in this study, was associated with better mental health and reduced stress in women with endometrial cancer. It’s thought to play a role in gut–brain communication and metabolic balance. ) , were linked to better mental health, lower stress, and improved physical well-being. Others, such as (sidenote: Christensenellales A family of gut microbes often associated with healthy metabolism and reduced inflammation. Here, its presence correlated with less bloating and gastrointestinal discomfort. ) and Desulfovibrionales, correlated with less bloating. Conversely, Veillonellales were tied to more gas and discomfort in women with benign conditions. Even sexual interest bore a microbial signature: vaginal Porphyromonas and Campylobacter were associated with lower libido, while Dialister appeared in women reporting higher sexual interest. These cross-links hint at a real (sidenote: Gut–brain–pelvic axis A concept describing the interconnected communication between the gut microbiome, the brain, and the reproductive organs. It suggests that microbial changes in the gut or vagina can influence mood, stress, and sexual health. ) , a biological dialogue connecting microbiota, mood, and intimate health.

Rethinking the role of microbes in cancer care

What makes this study stand out is its integration of patient experience with molecular biology, a rare bridge between the clinic and the lab. Rather than viewing the microbiome as a passive bystander, the data suggest it may be an active participant in symptom expression and recovery. In the future, mapping these microbial patterns could help predict which patients are most likely to struggle with vaginal or gastrointestinal side effects during cancer treatment, or whose emotional well-being might be at risk.

It also opens the door to precision microbiome interventions, from targeted probiotics to dietary strategies, designed not just to fight disease, but to restore comfort, intimacy, and resilience in women navigating endometrial cancer and its aftermath. As the lead authors put it, the microbes of the vagina and gut may soon become “vital signs” of how a woman feels, not just what disease she carries.