Antibiotics, a double-edged sword when managing skin disease

The effects of antibiotics on the skin microbiota have been studied mainly in the context of acne treatment. They may lead to several adverse outcomes including microbiota disruption, bacterial resistance and a risk of further infections hitting the skin or other body sites.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Author

Long regarded mainly as a source of infection, the human skin microbiota is nowadays commonly accepted as an important driver of health and wellbeing.1 By promoting immune responses and defense, it plays a key role in tissue repair and barrier functions by inhibiting colonization or infection by opportunistic pathogens.2

To each skin site, its own microbiota

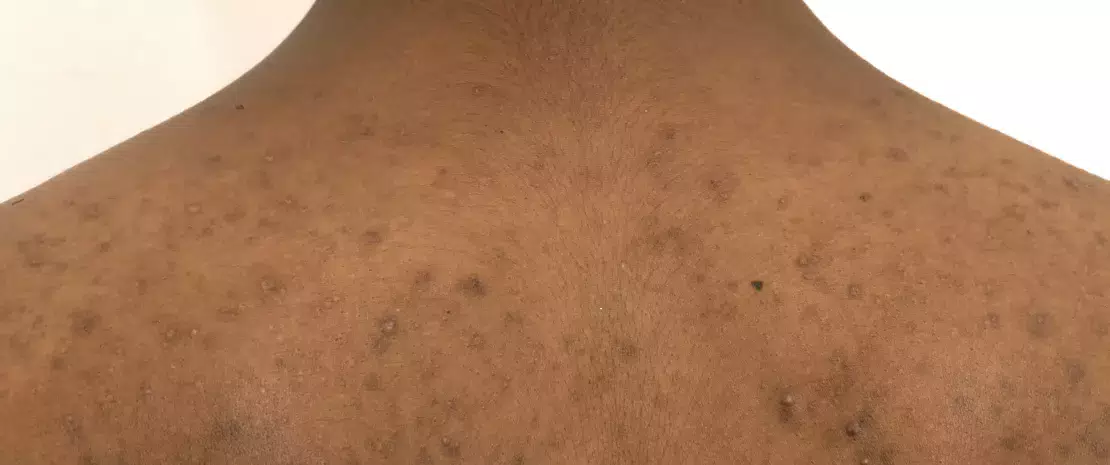

The skin microbiota harbors millions of bacteria, as well as fungi and viruses in lower relative abundances. Corynebacterium, Cutibacterium (formerly known as Propionibacterium), Staphylococcus, Micrococcus, Actinomyces, Streptococcus and Prevotella are the most common genera of bacteria encountered on the human skin.3 However, the relative abundance of bacterial taxa greatly depends on the local microenvironment of the particular piece of skin being considered, and especially on its physiological characteristics, i.e., whether it is sebaceous, moist or dry. Hence lipophilic Cutibacterium species dominate sebaceous sites while Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium species are particularly abundant in moist areas.4

From physiology to pathology, the ambivalent role of C. acnes

The aerotolerant anaerobe C. acnes is one of the most abundant bacterial species in the skin microbiota. It has been implicated in acne, a chronic inflammatory disorder of the skin with complex pathogenesis.5 In contrast with previous thinking, recent studies indicate that C. acnes hyperproliferation is not the only factor implicated in the development of acne.6 In fact, a loss of balance between the different C. acnes strains, together with a dysbiosis of the skin microbiota will trigger acne.6 Moreover, interactions between S. epidermidis and C. acnes are of critical importance in the regulation of skin homeostasis: S. epidermidis inhibits C. acnes growth and skin inflammation. In turn, C. acnes, by secreting propionic acid which participates, among other things, in maintaining the pilosebaceous follicle acidic pH, inhibits the development of S. epidermidis. Malassezia, the most abundant skin fungus is also thought to play a role in refractory acne by recruiting immune cells, though its involvement needs to be further explored.6

Antibiotics in atopic dermatitis: friend or foe?

In atopic dermatitis (AD), patients display skin microbiota dysbiosis characterized by an overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus, which is thought to play a decisive role in the manifestation of AD.14 Though antibiotic treatments have not demonstrated any efficacy in managing AD15 and though they are liable to induce bacterial resistance and result in a deleterious impact on skin commensals,14,16 they are nevertheless commonly used.

Acne treatment, an important source of antibiotic resistance

Despite being used routinely to treat acne, topical and oral antibiotics have proved to be problematic in several ways. A first concern expressed by experts is the disruption to the skin microbiota, although precise data on the subject remain scarce. In this vein, a recent longitudinal study compared the cheek microbiota of 20 acne patients before and after six weeks of oral doxycycline therapy. Interestingly, antibiotic exposure was associated with an increase in bacterial diversity; according to the authors, this could be due to a diminished colonization by C. acnes, which would liberate space to allow the growth of other bacteria.7

Dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics than any other specialists. Two thirds of these prescriptions are for acne.8

However, the most significant concern over the use of antibiotics for acne treatment relates to bacterial resistance. First observed in the 1970s, it has been a major worry in dermatology since the 1980s.8 C. acnes resistance is by far the most documented: the latest data point to resistance rates reaching over 50% for erythromycin in some countries, 82-100% for azithromycin and 90% for clindamycin. As for tetracyclines, although still largely effective against the majority of C. acnes strains, their resistance rates are rising, ranging from 2% to 30% in different geographic regions.9 And antibiotic resistance is not limited to C. acnes: while topical antibiotics used by acne patients (especially as monotherapy) have been shown to increase the emergence of resistant skin bacteria such as S. epidermidis, oral antibiotics have been associated with the increased emergence of antibiotic-resistant oropharyngeal S. pyogenes.8,10 In addition, increased rates of upper respiratory tract infection and pharyngitis have been reported as being associated with the antibiotic treatment of acne.11,12

Expert opinion

Antibiotics kill sensitive skin bacteria (Cutibacterium acnes), while concurrently leading to “holes” in the microbiota, which resistant bacteria will fill. This results in cutaneous dysbiosis and the overexpression of multidrug-resistant bacteria. 60% of patients treated for acne have macrolide-resistant C. acnes strains, and 90% of Staphylococcus epidermidis strains are also resistant to macrolides. The use of antibiotics can also have consequences in orthopedic surgery, where many macrolide-resistant strains of C. acnes are similarly observed. During an operation (a hip prosthesis, for example), there is a risk of causing an abscess. This will be all the more difficult to treat, as this bacterium secretes biofilms that adhere to the prosthesis. It is therefore essential, if promoting the selection of resistant bacteria is to be avoided, that the use of topical antibiotics be limited as far as possible (a maximum course of 8 days).

A call for a limited use of antibiotics in acne

The potential consequences of antibiotic resistance triggered by acne treatment are numerous: failure of the acne treatment itself (see clinical case), infection by opportunistic pathogens (locally or systemically), and the dissemination of resistance among the population.8 Despite this, the levels of antibiotic prescriptions for acne remain high and for longer durations than recommended in the guidelines.13 Against this background of mounting concerns, experts are calling for a more limited use of antibiotics in the treatment of acne.13 In particular, a strategy has been proposed in this regard by the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne (see box below).

Strategies from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne to reduce antibiotic resistance in Cutibacterium acnes and other bacteria

First line therapy5

- Combine topical retinoid with antimicrobial (oral or tropical)

If addition of antibiotic is needed:

-

Limit to short periods; discontinue when only slight or no further improvement

-

Oral antibiotics should ideally be used for 3 months

-

Coprescribe benzyl peroxide-containing product or use as washout

-

Do not use as monotherapy • Avoid concurrent use of oral and topical antibiotics

-

Do not switch antibiotics without adequate justification

Maintenance therapy

-

Use topical retinoids, with benzoyl peroxide added if needed

-

Avoid antibiotics

Clinical case

by Pr. Brigitte Dreno, MD, PhD

-

A teenager consulted his dermatologist for facial acne (forehead, chin, and cheeks). He received a topical erythromycin-based treatment.

-

4 to 5 weeks after starting treatment, a new proliferation of papules and pustules appeared on his face. He went back to his doctor, who prescribed oral erythromycin.

-

1 month later, the patient returned to see his doctor because his acne had extended to his neck (profuse impetigo). The doctor took a sample from one of the pustules for a culture test.

-

The culture test came back positive for Staphylococcus, and the antibiogram indicated a resistance to macrolides. The doctor prescribed benzoyl peroxide, which gave remission within 10 days.