Towards worldwide redefinition of healthy vaginal microbiota

Is our view of the vaginal microbiota too bacteria-centric and ethnocentric? So suggests an opinion piece 1 written by renowned researchers calling for more research into the diversity of vaginal microbiota worldwide and highlighting its key role in women’s health and in preventing certain infections.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

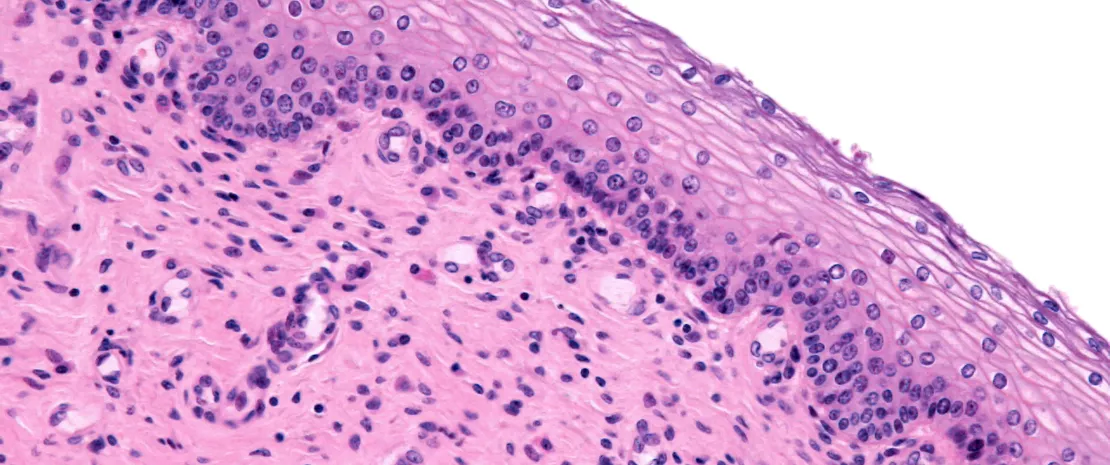

The vaginal microbiome is crucial to gynecological health. But with one main difference: unlike many other microbiomes, where healthy means diverse, the “gold standard” for a healthy vaginal flora is (at present) an ample predominance of Lactobacilli.

The predominance of Lactobacilli, particularly L. crispatus, is currently associated with increased protection against certain infections, including sexually transmitted infections, as well as a lower risk of complications during pregnancy. This may explain why their predominance serves as the benchmark for a healthy vaginal microbiota.

However, in an opinion article on vaginal health, a group of international experts have pointed out the limitations of the current five

(sidenote:

Five community state types (CST)

- CST I dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus,

- CST II dominated by L. gasseri,

- CST III dominated by L. iners

- CST V dominated by L. jensenii

- and the more diverse CST IV, which is not dominated by Lactobacillus but by a group of anaerobic bacteria, including Gardnerella, Atopobium, Prevotella, and Finegoldia.

)

classification: it does not reflect the full biology and functionality of the vaginal microbiome. The authors cite the Belgian Isala study, where 10.4% of participants displayed a co-dominance of L. crispatus (CST I) and L. iners (CST III), suggesting that CSTs may co-exist in some women. Another limitation is that the role of fungi, eukaryotes, archaea, and viruses remains largely unexplored.

Data mainly from wealthy countries

To illustrate their point, the authors considered bacterial vaginosis. This condition is diagnosed using the (sidenote: Nugent score A diagnostic scoring system used to assess bacterial vaginosis based on the presence and proportions of certain bacteria in a Gram-stained vaginal sample. ) or the (sidenote: Amsel criteria The Amsel criteria might provide a more clinical diagnosis of BV because they are based on the following four signs: vaginal fluid pH above 4.5, positive whiff test (foul odor after adding 10% potassium hydroxide – KOH), presence of clue cells, and abnormal vaginal discharge. At least three of these signs must be present before BV is diagnosed. ) , but these systems suffer from biases, particularly geographical biases.

Bacterial vaginosis is a very common cause of vaginal discharge among women of reproductive age.

The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis varies across countries and population groups, but according to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, the global BV prevalence among women of reproductive age ranges from 23 to 29%. Bacterial vaginosis increases the risk of contracting and transmitting infections such as HIV and other STIs and, if left untreated, can have adverse effects during pregnancy. 2

In 2024, the WHO published Recommendations for the treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Candida albicans, bacterial vaginosis and human papillomavirus 3 (anogenital warts) to provide evidence-based clinical and practical recommendations on case management of bacterial vaginosis.

Is the lower presence of Lactobacilli and higher frequency of vaginosis in black and Latin American women (vs. women of Asian or European origin) in the United States real or simply due to methodological limitations? Could socioeconomic inequalities between populations explain some of the differences? What about different behaviors, such as douching, a noted risk factor for vaginal dysbiosis? What about the many American women classified as African American even though (more than) half of their ancestors were white Europeans?

Ultimately, what do we really know about the make-up of a “healthy” and balanced vaginal microbiota in women with distinct geographical and ethnic origins?

Projects on every continent

The authors highlight the lack of studies in low- and middle-income countries, despite a growing number of initiatives attempting to fill this gap:

- The Vaginal Human Microbiome Project (VaHMP) maps data on the vaginal flora of women from different ethnic backgrounds in the United States;

- The VIRGO database supplements the US data with data from six countries on different continents;

- The Vaginal Microbial Genome Collection (VMGC) contains data from 14 countries;

- The Vaginal Microbiome Research Consortium has a specific section for Africa and Bangladesh.

Another approach is citizen science (public contribution to vaginal microbiome research around the world using a bottom-up, local approach), such as the authors’ Isala project on vaginal flora. Following its success in Belgium (more than 6,000 applications for 200 women sought), the initiative has been extended to a global network of partners on different continents (the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Europe), promoting collaboration between teams.

The authors consider all these initiatives necessary for a more complete understanding of a “healthy” vaginal microbiome.

How to talk about women's health: Pr. Graziottin's advice

These advances may also help us to better understand the conditions that promote a balanced vaginal microbiota, in particular by further investigating the protective role of certain species, such as Lactobacillus crispatus, and by rigorously evaluating the benefits of probiotics in this equation.