From birth to death, an exposome with different consequences on our health

Our sensitivity to the environment changes throughout life. From pregnancy onward, the exposome shapes immunity, influences the infant’s microbiota, and affects their future risk of asthma or allergies. During adolescence, it impacts mental and skin health. In adulthood, it influences inflammation and overall well-being. In seniors, it can either preserve or impair longevity, as shown in studies on the microbiota of centenarians.

Discover how every stage of life interacts with the exposome.

- Learn all about microbiota

- Microbiota and related conditions

- Act on your microbiota

- Publications

- About the Institute

Healthcare professionals section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

Table of contents

Table of contents

First 1,000 days

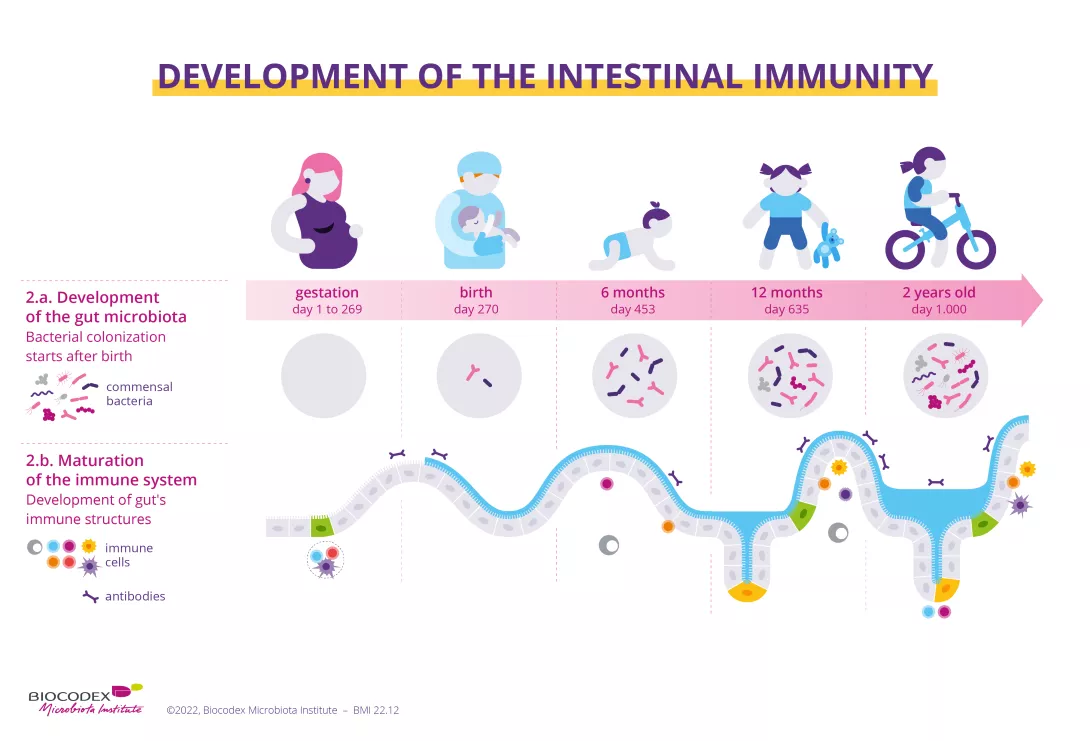

We’ve known for some time that the microorganisms in the gut microbiota are essential to the development of our immune system. However, other mechanisms related to early exposure of the fetus and young child to environmental factors may be involved 33.

Perinatal period

- Pregnancy: a mother’s microbiota (gut, skin, lung, and perhaps placental microbiota) appears to have important effects on the maturation of the immune function in her offspring. For example, one study showed that exposing pregnant women to bacteria from barns reduced the risk of their children subsequently developing asthma. The placental microbiota, which more closely resembles the maternal oral microbiota than the vaginal or gut microbiota, may play a role in this maturation.

- Birth: babies born vaginally are colonized by microbes similar to those present in their mother’s vagina. They also have a richer and more diverse gut microbiota than those born by Cesarean section, which is associated with a lower risk of asthma.

- Breastfeeding

Other factors in the perinatal exposome (antibiotic treatment, breastfeeding, diet, etc.) are also thought to be involved.

Tiny bacteria, big risks: how vaginal microbes shape pregnancy health

Early childhood

Since the middle of the last century, the trend towards more affluent lifestyles and more modern and “hygienic” habitats has altered our exposure to microbes. These alterations may predispose children to chronic inflammatory diseases.

Indeed, there’s strong evidence that early exposure to rich, diverse microbial populations plays a protective role, provided it occurs early in life. This period is known as the “window of opportunity”.

Various studies have counter-intuitively shown that the presence of pets, rodents, fungi, or bacteria in the living environment of infants and toddlers improves the bacterial diversity of their microbiota and may protect them from asthma.

Dogs and dust microbiota in asthma prevention: a masterstroke?

Childhood and adolescence

The value of the exposomic approach was highlighted by a study of 504 children aged 6 to 9, who were followed for eight years. Researchers measured the impact of different exposures (diet, physical activity, sleep, air pollution, socio-economic status) on blood markers (metabolites).

Exposome score

For each child, the researchers calculated an “exposome score” measuring the overall impact of various exposures on health.

The results show that this score is associated with 31 metabolites, 12 of which were not linked to any individual exposure. This indicates that environmental and lifestyle exposures do not exert their physiological effects in isolation.

Rather, there’s a complex interaction between external exposures and the associated internal physiological responses.

What’s more, a high exposome score is associated with lower levels of acetate, a (sidenote: Short chain fatty acids (SCFA) Short chain fatty acids (SCFA) are a source of energy (fuel) for an individual’s cells. They interact with the immune system and are involved in communication between the intestine and the brain. Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:25. ) produced by the gut microbiota. Studies suggest that acetate may play a beneficial role in metabolic, cardiovascular, and neuronal health 34 .

After all, eating Big Brother's snot might not be a bad idea

Acne

Another study, this time on teenagers, showed that numerous lifestyle factors (consumption of skimmed milk and whey protein supplements, stress, pollutants, medication, climate factors, etc.) had a clear impact on the progression and severity of acne, and on the efficacy of treatments.

Skin care products and cosmetics are part of the external exposome. They can activate inflammation and cause acne flare ups by altering the skin barrier and the balance of the skin microbiota, promoting sebum secretion, modifying microbes, and activating the innate immune system 35.

Mental health

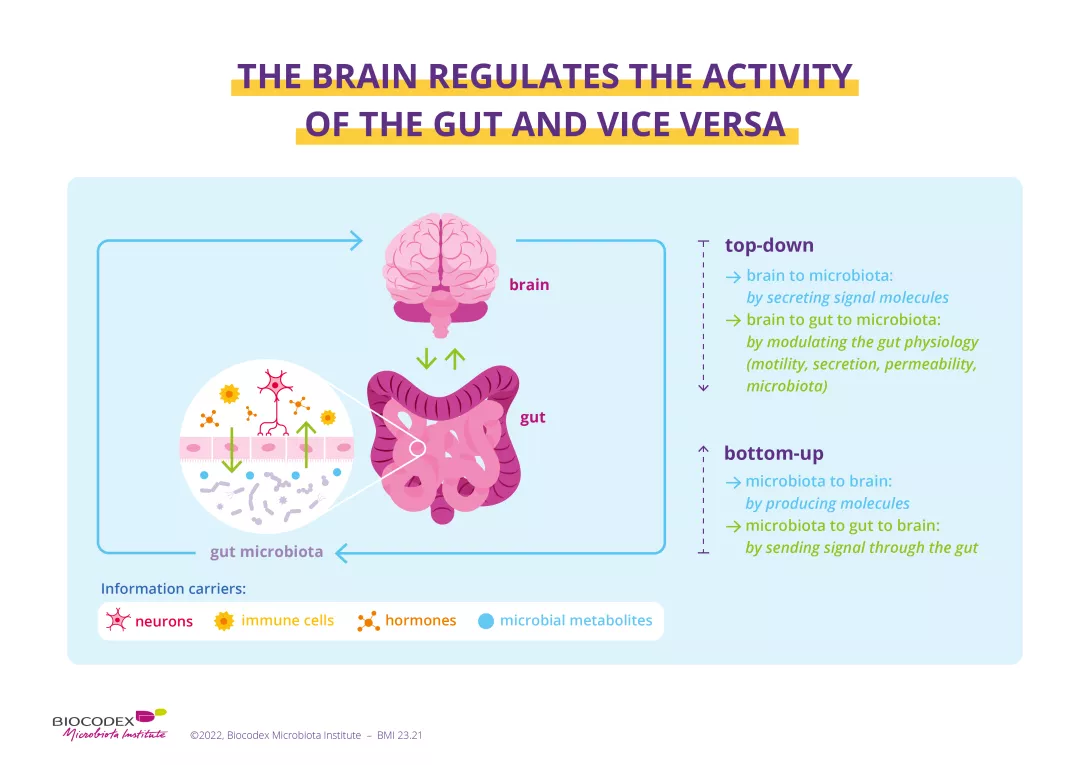

We also know that during adolescence, stress – often more intense than at other times of life – and the increased production of androgens (such as testosterone) are likely to modify the microbiota and, consequently, the gut-brain axis.

Research suggests that these internal exposome changes may play a role in the emergence of psychiatric illnesses, many of which first appear during adolescence 36.

What role does the microbiota play in the gut-brain axis?

Adulthood

It’s becoming increasingly clear that the gut microbiota is involved in various aspects of physical and mental well-being, and that its structure and function largely depend on lifestyle.

While the impact of the exposome is crucial early in life, we know that its harmful effects can continue into adulthood. A Western diet (low in fruit, vegetables, and whole grains; high in animal products and ultra-processed foods) can, for example, disrupt the biofilm and gut barrier, making the gut more permeable.

This can allow pieces of bacteria (endotoxins or lipopolysaccharides) to enter the bloodstream, leading to chronic low-grade inflammation, with potentially harmful metabolic and behavioral consequences. Conversely, a diet rich in fiber and phytochemicals from plants can promote microbial diversity and reduce oxidative stress and inflammatory load.

An unbalanced diet combined with stress, a lack of contact with nature, a microbe-poor environment, and a lack of outdoor physical activity can also alter the microbial diversity of the gut and skin microbiota. A lessdiverse microbiota means immune dysfunction and chronic inflammation, which can affect all organs and pave the way for chronic disease.

How to keep a healthy microbiota?

Among seniors

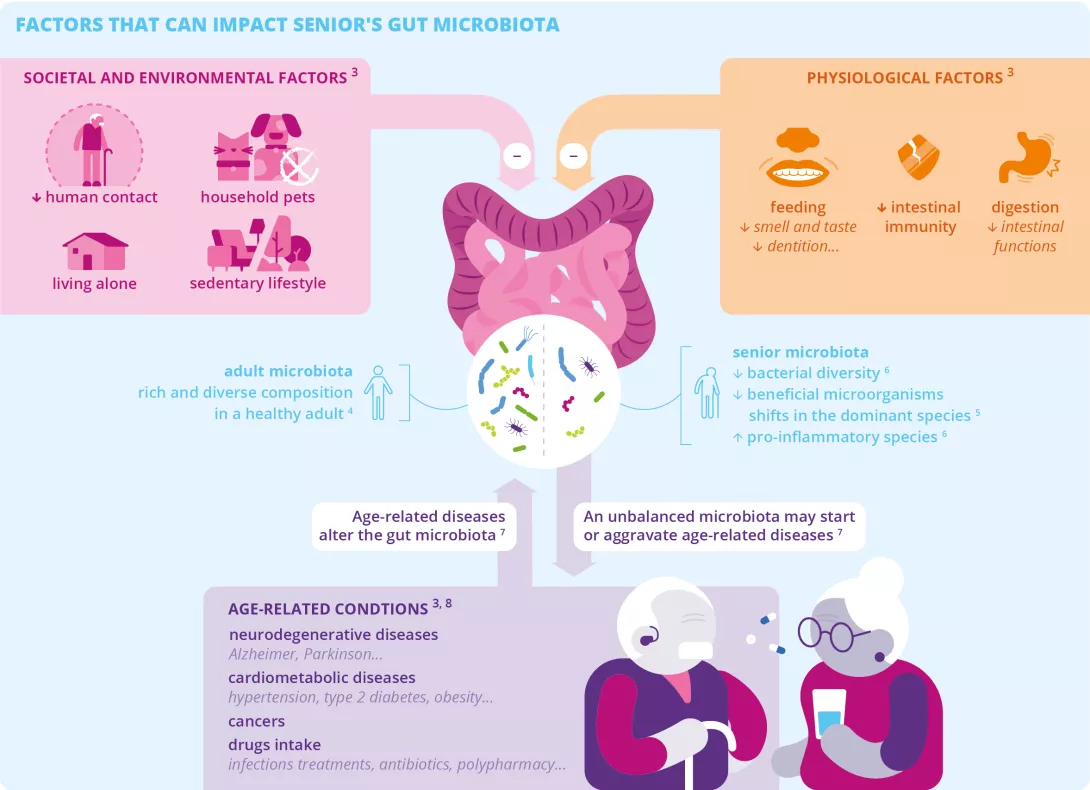

Aging is generally associated with alterations in the gut microbiota. Over time, the gut microbiota tends to lose its diversity and balance (dysbiosis), contributing to an accentuation of inflammatory processes and increased susceptibility to diseases that make the elderly more fragile.

On the other hand, maintaining a balanced microbiota over time promotes a healthy metabolism and immune system, and preserves heart, bone, and cognitive health.

While the causes of microbiota alterations with age are still under research, the study of centenarians’ microbiota tells us that certain exposome factors may be involved.

Eating habits, such as adherence to the Mediterranean diet (rich in fiber and antioxidants), are correlated with gut microbial species linked to longevity 38,39. Physical activity, not smoking, and satisfactory working conditions may also play a part.