Autistic children have distinct bacterial and fungal populations in the intestines, as well as oral dysbiosis. These two complementary research areas could help structure diagnostic approach and therapeutic care.

DISRUPTED GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

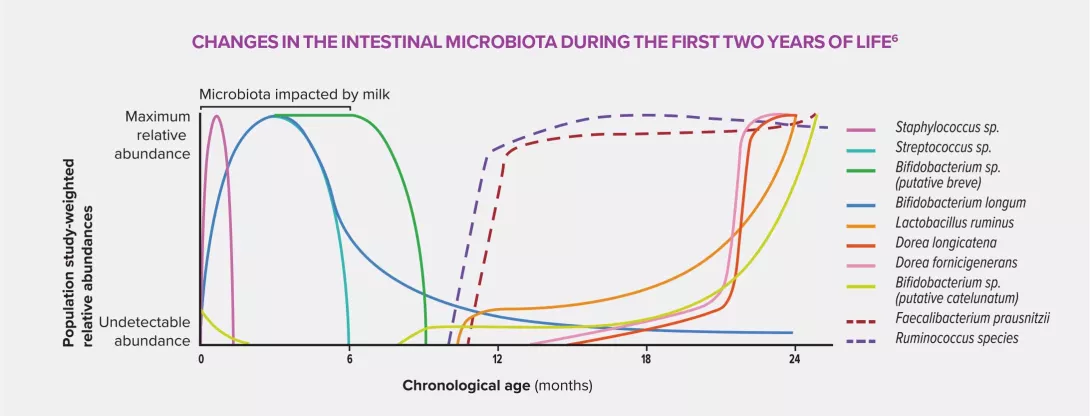

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that generally appears in early childhood, and is characterized by behavioral disorders: difficulties in establishing social relationships, communication problems and OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorders). The mechanisms of the disease remain unclear, but the recurrent presence of gastrointestinal problems in autistic children could suggest a possible link with the intestinal microbiota. Studying this hypothesis could help clarify etiology, which is currently based mainly on genetic and environmental factors.

BACTERIAL ALTERATIONS…

Some studies, such as those of an Italian team, have tried to validate the hypothesis of a dysbiosis.7 Fecal samples from 40 children with severe autistic disorders and 40 “neurotypical” controls led to the characterization of the bacterial populations by amplification of 16S rRNA genes. The analyses confirm the pertinence of the original hypothesis: a significant increase in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, traditionally associated with an increased risk of developing inflammatory disorders, was observed in autistic children. At the genus level, a depletion of Alistipes, Bilophila, Dialister, Parabacteroides and Veillonella, and an increase in Collinsella, Corynebacterium, Dorea and Lactobacillus were observed. In autistic subjects suffering from constipation (a symptom of gastrointestinal problems that is common in this pathology), an abundance of Escherichia, Shigella and Clostridium was also observed.

… AND FUNGAL ALTERATIONS

Analysis of the fungal community also demonstrated disparities between the autistic and control subjects, with the former having a twofold higher proportion of Candida. This observation must be tempered, as this type of fungus is naturally found in humans, to the point that the discrepancy is not very significant. Fungal dysbiosis seems nevertheless confirmed. It could influence bacterial development and vice versa, as the two communities develop within the same microbiota.

IS THE ORAL MICROBIOTA ALSO INVOLVED?

The intestinal microbiota is not the only one being implicated in the development of autism. Researchers are also examining the microbial populations of ENT areas, which contain a large diversity of taxa (more than 700 in the oral cavity alone) and act as a reservoir of infections for other parts of the body, including the central nervous system. Since previous works have shown oral dysbioses in patients with Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, MS, or migraine, researchers decided to characterize the oral microbiota of autistic children to characterize any microbial specificities.9

THE ORAL CAVITY, A SPECIAL ENVIRONMENT

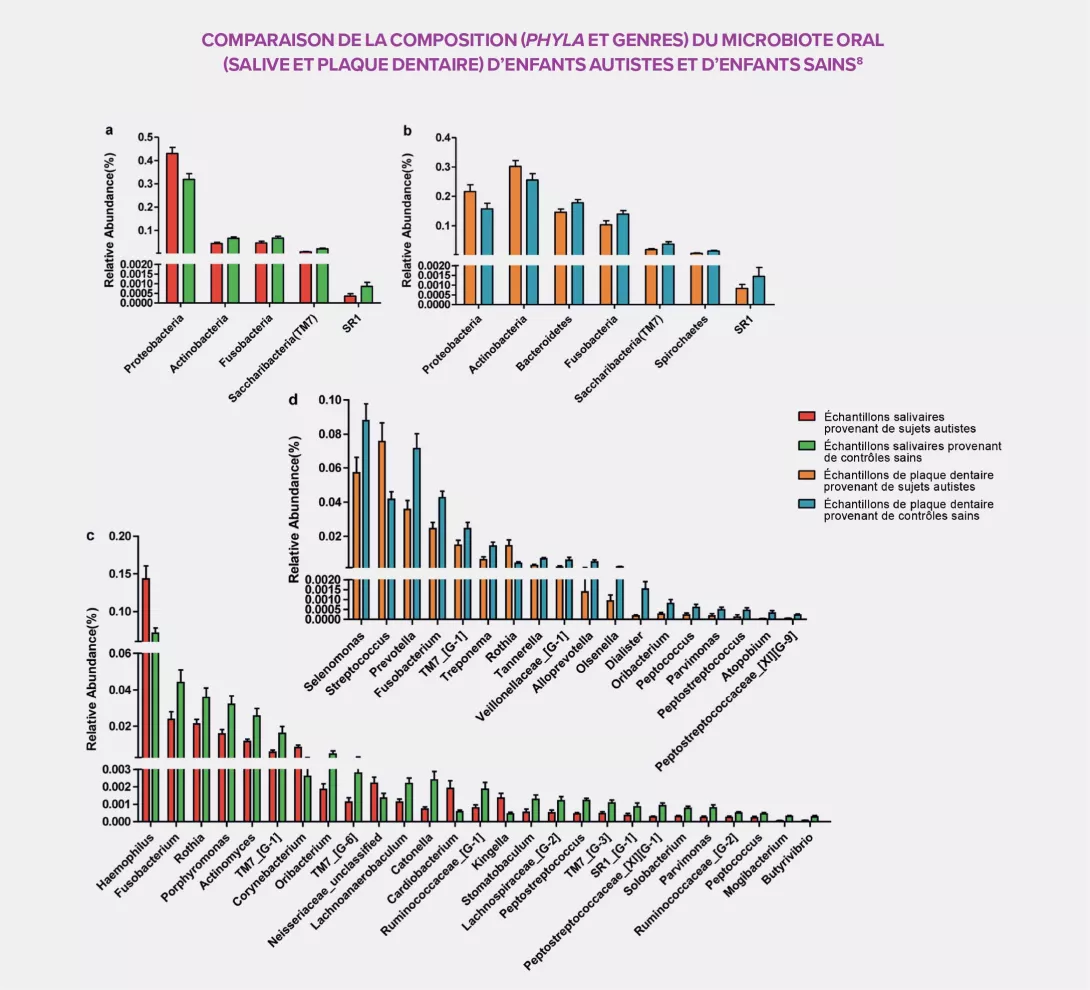

The peculiarity of the oral cavity is that both soft tissue (mucous membranes) and hard tissue (teeth) coexist in it. Sampling of both saliva and dental plaque provided a more detailed identification of the bacterial populations of 111 samples taken from 32 autistic children and 27 controls. Like with the intestinal microbiota, large differences were observed between the two groups of participants. The oral microbial community of autistic subjects is characterized by an overall bacterial depletion and a rise in pathogens such as Haemophilus in the saliva and Streptococcus in the dental plaque, as well as a decrease, in both areas, in several commensal bacteria: Prevotella, Selenomonas, Actinomyces, Porphyromonas and Fusobacterium. The dental plaque also displays a significant decrease of all Prevotellaceae, a family capable of interacting with the immune system, and a high concentration of Rothia, a bacterium frequently associated with dental diseases in the literature.

THE MICROBIOTA: A NEW DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC TOOL IN PSYCHIATRY?

Thanks to the oral bacterial populations identified in autistic disorder, a diagnostic model has been developed based on the main oral biomarkers. This tool, which displayed a 96.3% efficacy rate with saliva, could prove particularly useful and relevant in modern psychiatry. This biological approach could complement the usual criteria derived mostly from DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), which is based on a consensus on clinical symptoms that are difficult to measure. More extensive investigations into the microbiota of autistic children could make possible new diagnostic approaches, and the development of innovative therapeutic strategies.