Do we not overestimate the importance of microbiota in the urogenital area?

In recent years we have come to understand the urogenital micro- biota more clearly. We now know that it can be a factor in infections, in urinary disorders related to the menopause and even in tumors. The urogenital microbiota and its disruptions must be taken into account in patient management and probiotics must be part of the therapeutic arsenal. Although probiotics are obviously not our only weapon, they are indispensable, since anti-infectious treatments do not treat the cause of recurrence, i.e. the dysbiosis.

What role do you think probiotics can play today against urinary tract infections?

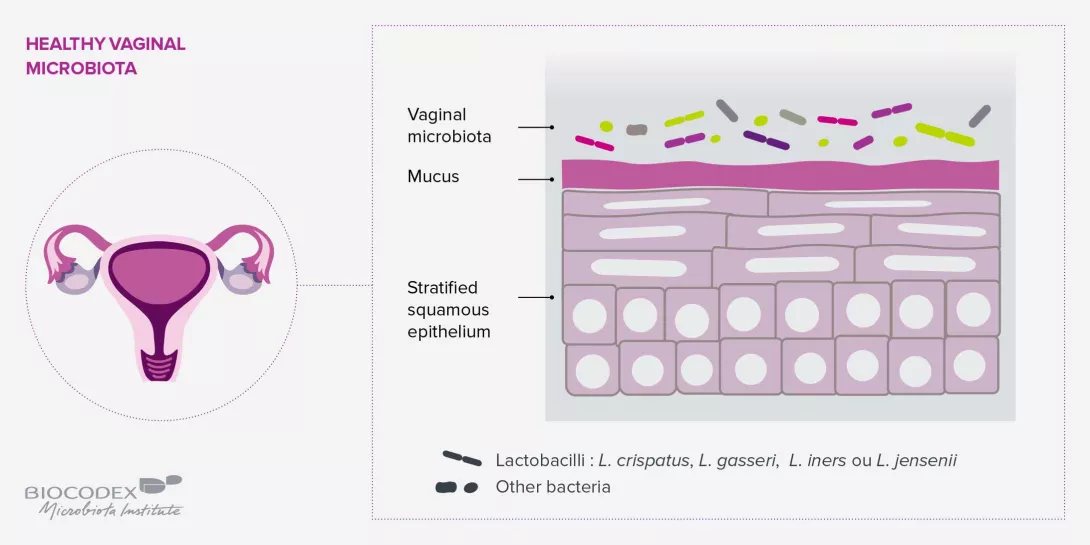

Urinary tract infections are closely linked to imbalances in three microbiomes: the urinary micro- biota, since urine is not sterile; the vaginal micro- biota, with which the urinary microbiota shares many similarities; and the gut microbiota, from which the pathogens involved in urinary tract infections originate (e.g. E. coli, which passes from the anus to the vulvar vestibule and then to the bladder). Conventional antibiotic treatment is justified for single UTI episodes. On the other hand, for recurrent UTIs (more than four episodes per year), it is essential, after having ruled out functional causes (e.g. a tumor of the bladder), to question the pa- tient about possible disorders of the gut microbiota (constipation, etc.) and/or vaginal microbiota, the latter acting as a protective barrier between the digestive and urinary systems. The prevention of recurrence involves treatment for three to six months with intestinal probiotics administered orally, if a dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota is present, and/or vaginal probiotics, ideally administered vaginally. These treatments may be combined with the use of cranberry, which reduces the level of E. coli in the bladder.

What about vaginal infections?

There are two types of vaginal infections: endogenous infections resulting from changes in endogenous microorganisms (bacteria or fungi) and exogenous infections contracted during sexual intercourse. For endogenous infections, in the case of a single episode, an antimycotic vaginal suppository or antibiotic treatment may suffice. However, where there is a risk of recurrence, the dysbiosis must be treated for several months with gynecological probiotics. Probiotics also have a role to play in exogenous infections, since the less balanced the vaginal microbiota, the greater the risk of acquiring a sexually transmitted infection (STI), and the higher the risk of an unfavorable outcome. For example, the papillomavirus is four to five times more likely not to be completely eliminated, and progresses more rapidly to potentially cancerous forms, when a dysbiosis exists. It is therefore important to test for an imbalance of the vaginal microbiota in infected women through a simple measurement of acidity (the pH should be between 3.5 and 4.5) and then by vaginal sampling where the pH is above 4.5. Where there is an imbalance, laboratory-tested and clinically approved probiotics should be prescribed. A vaginal dysbiosis also increases the risk of contracting HIV. Although the acidity of lactobacilli helps destroy the virus, an inflammatory state increases the presence of lymphocytes, the cells targeted by HIV.

Lastly, what can we expect from vaginal micro- biota transplants?

The results of just over twenty cases of vaginal microbiota transplants have been published. Al- though these results are interesting, they are not yet conclusive. The idea of treating recurrent bac- terial vaginosis through a microbiota transplant still raises concerns as regards the criteria for selecting donors–particularly since the absence of symptoms does not mean that the donor’s flora is balanced–and the indications for the recipient. It will most likely be known within a year or two whether vaginal microbiota transplants can be used as a last resort.

Is the gut microbiota a good indicator of longevity?

Is the gut microbiota a good indicator of longevity?