Available in 7 languages (English, French, Spanish, Russian, Polish, Turkish, and Portuguese), this online international hub offers you the latest scientific news and data about microbiota including the Institute’s exclusive content such as Microbiota magazine, thematic folders, continuing medical education (CME) courses and interviews with experts.

A useful and trustful partner for HCPs

In a dedicated section for HCPs, you will also find practical and educational infographics such as: “What are probiotics?” or “what you need to know about the 6 microbiota of the human body?”, that you can easily download and share with your patients. Care to share other information with your patients? Invite them to discover the lay public section of the website through dedicated online journeys, where they can find updated, useful and understandable content.

Stay tuned, stay up to date!

Also available on this hub, congress calendars where you can find the next events about microbiota. And after your journey on the website, don’t forget to register online to receive the “Microbiota Digest”, a monthly newsletter with the latest news about microbiota. Want to share a publication? To follow a Conference live-tweet (WGO, ESPGHAN, etc.)? Or browse through Microbiota Institute’s new Twitter account (@Microbiota_Inst) designed to reach the widest community of health professionals who want to be up to date with the latest information on the microbiota field. By providing healthcare professionals with the latest scientific news and data, but also a variety of educational tools and services, Biocodex Microbiota Institute’s website aims to help healthcare professionals improve their patient’s understanding of their conditions on an everyday basis.

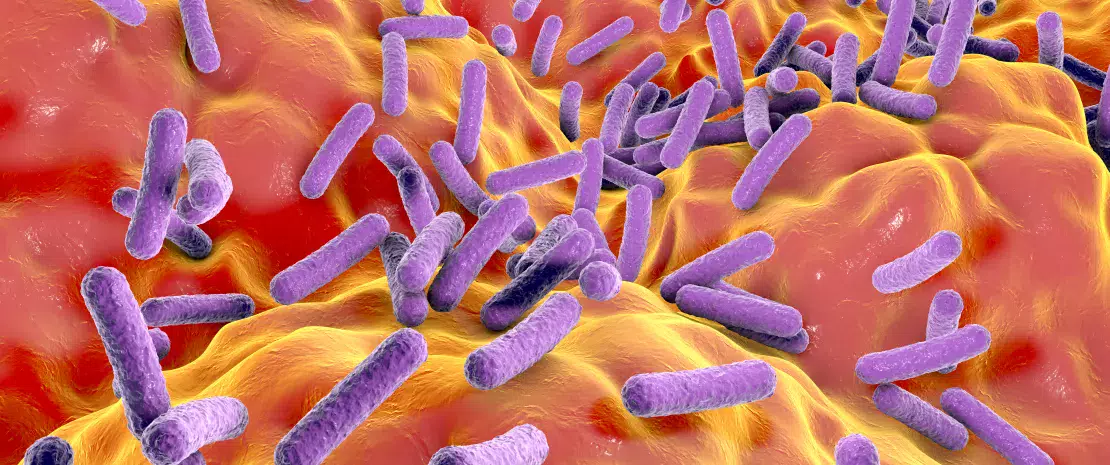

About the Microbiota Institute

The Biocodex Microbiota Institute is an international scientific institution that aims to foster health through spreading knowledge about the human microbiota. To do so, the Institute addresses both healthcare professionals and the general public to raise their awareness about the central role of this still little-known organ of the body.