Have you heard of "dysbiosis"?

Dysbiosis refers to a breakdown in the delicate balance between the billions of microorganisms that make up our human microbiota and in their relationship with our body. There are a range of factors that lead to dysbiosis, including genetics, an unbalanced diet and antibiotics, with most cases involving several factors. Today, scientific research has demonstrated that dysbiosis of the most extensively studied microbiota—the gut microbiota—as well as other microbiotas such as the vaginal, skin and lung microbiotas, is associated with various diseases, from irritable bowel syndrome to metabolic disorders like obesity, or even chronic sinusitis and eczema. But how does the microbiota become imbalanced? What impacts does dysbiosis have on our health? How can we rebalance the microbiota?

Read on to find out!

What is dysbiosis?

First, let's look at the word itself: "dysbiosis". The etymology of this scientific term is actually very straightforward! In Greek, the word bios means "living" and the prefix dys- means "bad".

"Dysbiosis" can be defined as a change in the composition and functioning of the microbiota. This change is the result of a combination of environmental factors and factors specific to each person1.

As microorganisms colonize all our body, a dysbiosis can be observed in:

- Gut microbiota: various diseases have been associated with intestinal dysbiosis: antibiotic-associated diarrhea14, gastroenteritis17, infantile colic44…

- Skin microbiota: the dysbiosis is often associated with pathological conditions (acne45, atopic dermatitis46)

- Vaginal microbiota: a vaginal dysbiosis is associated to a bacterial vaginosis1, a candidiasis47, a reduced fertility48 or a higher risk of premature birth1

- ENT (ear, nose, throat) microbiota: various diseases could be associated with imbalanced of the oral, auricular or nasopharyngeal microbiota

- The pulmonary microbiota: dysbiosis may participate to the development of winter respiratory infections49, asthma50, cystic fibrosis51

- The urinary microbiota: studies published to date have demonstrated the role the urinary microbiota may play in urinary tract infections52

Dysbiosis in the spotlight: the gut microbiota

Our gut microbiota is the human body's main microbiota.2 It contains at least 1000 different species3 of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi and viruses. The Firmicutes group (which includes the well-known "good bacteria", lactobacilli) and the Bacteroidetes group together account for 70–90% of the bacterial community in our gut.2,4 Our microbiota also contains Actinobacteria, which include bifidobacteria, known for their beneficial effects. Other microorganisms in our microbiota can make us ill. These are referred to as " (sidenote: Pathogen A pathogen is a microorganism that causes, or may cause, disease. Pirofski LA, Casadevall A. Q and A: What is a pathogen? A question that begs the point. BMC Biol. 2012 Jan 31;10:6. ) ", but they are in the minority.2 Dysbiosis involves one or more of the following phenomena:

- A significant change in the relative proportions of the major bacterial families, in particular a loss of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria;5

- A reduction in or total loss of the useful microorganisms that usually live in our microbiota (known as "commensal" microorganisms);1

- A decrease in the diversity of the microorganisms found in the microbiota, meaning there are fewer different species;5

- The growth of potentially pathogenic microorganisms within the microbiota.1,5

As a result, our microbiota is weakened and the "bad" bacteria take over from the "good" bacteria.2 It becomes harder for the microbiota to protect the body from attack and to carry out its essential roles relating to our health and well-being.1,6

1000 It contains at least 1000 different species of microorganisms.

What does a dysbiosis look like?

While dysbiosis itself is not considered a disease, it has been linked to various health problems and may contribute to the development or exacerbation of certain medical conditions.

Our own unique microbiota imbalance

However, "dysbiosis" is not a universal term that can be applied to anyone in any circumstance! 1 In fact, the composition of our microbiota is particular to each person, and is influenced by our genes and by the microorganisms that colonised our body during our first years of life ("microorganisms" are defined as "living organisms that are too small to be visible with the naked eye. This includes bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea, protozoa and so on, collectively known as ' (sidenote: https://microbiologysociety.org/why-microbiology-matters/what-is-microbiology.html ) '). The microbiota varies so considerably between individuals that it could well be as unique to each of us as our fingerprints.7 What's more, it can change depending on our age, health, stress levels and diet, as well as where we live and any medicines we are taking.8 This means that each of us can experience our own specific dysbiosis when our microbiota becomes imbalanced and no longer functions correctly within our body.1

So what does a balanced microbiota look like?

The prefix dys- in "dysbiosis" is the opposite of eu- ("good") or sym- ("with"). So we talk about "eubiosis" or "symbiosis" when our microbiota is in good health: when it is interacting harmoniously with our body and its microbial community is in balance.1

The relationship between our body and the billions of microorganisms that make up our microbiota is mutually beneficial.9 Each has its role to play: the body provides "bed and board" for the microorganisms, while the latter contribute to numerous important functions within the body, including digestion, nutrient assimilation, keeping the intestinal walls impermeable and fighting unwanted germs.2,8,10 Teamwork in action!

The various microorganisms that populate the microbiota community — including potentially pathogenic ones — are present in sufficient numbers and proportions to cohabit peacefully and fulfil their beneficial functions within the body. However, the delicate balance between the microbial ecosystems within our body can be upset, at which point eubiosis turns to dysbiosis.8

What causes dysbiosis?

As its definition suggests, dysbiosis occurs under the influence of numerous very different and often interrelated factors.5 Among these are the following:

Factors linked to the individual themselves, such as:

- Genetics;1

- Age;11

- Certain diseases and injuries;1

Factors linked to the individual's environment, such as:

- Taking medicines: antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, etc.;2,5

- Infections;12

- Lifestyle: unbalanced diet or changes in diet, stress, smoking, poor hygiene, etc.;1,5,8

- Pollution.8

What can cause a dysbiosis ?

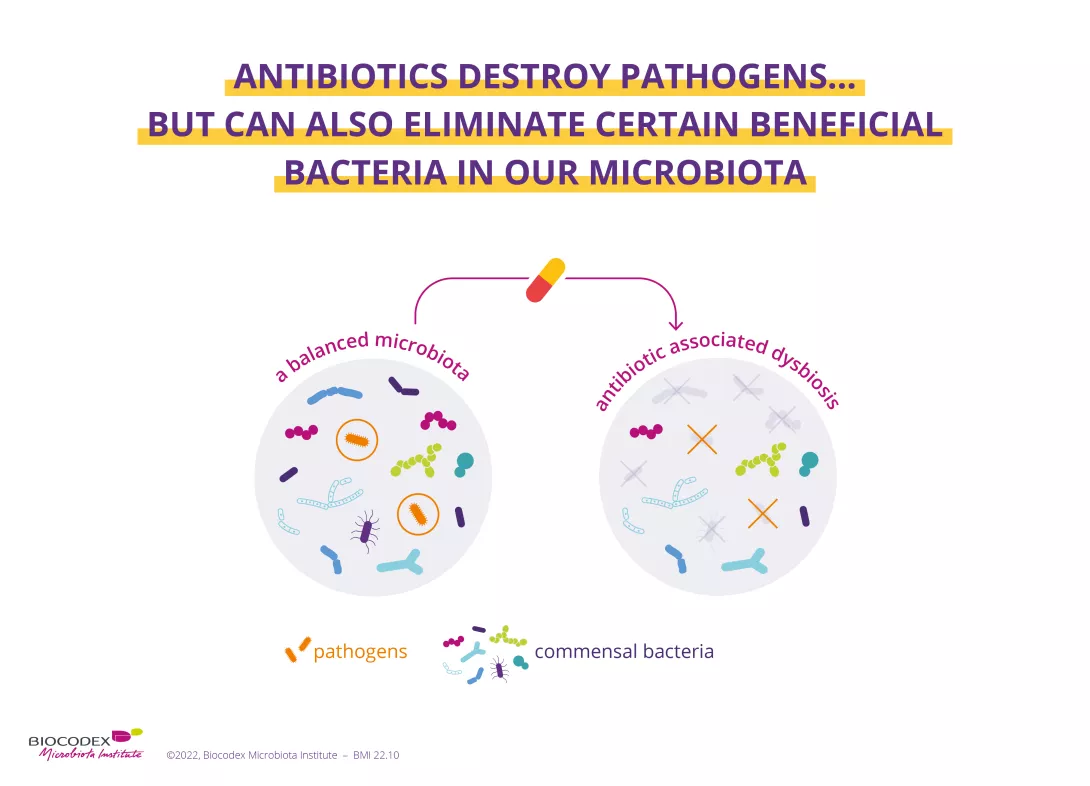

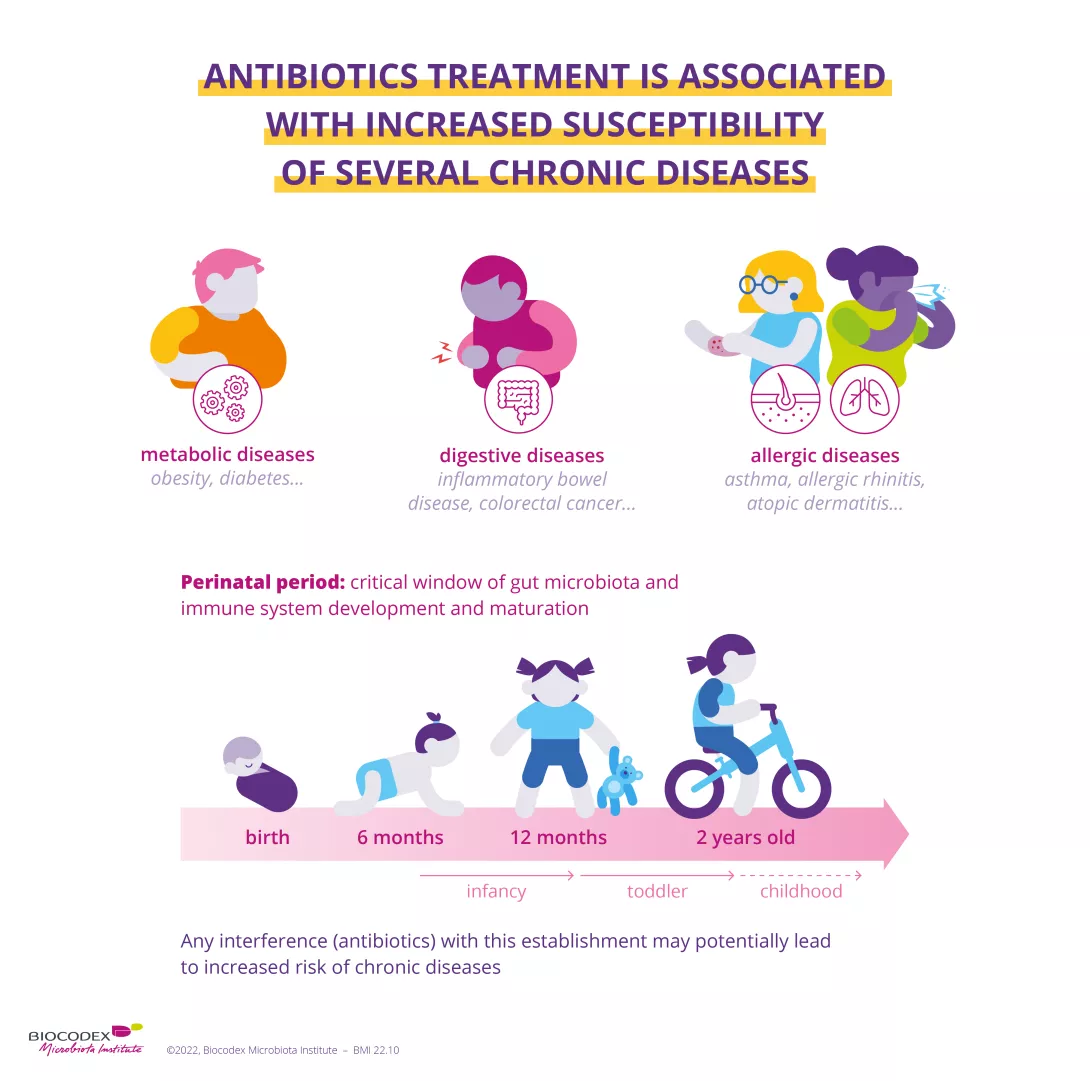

Antibiotics were one of the most important therapeutic breakthroughs of the twentieth century. Since penicillin was discovered in 1928, they have saved millions of lives.13 However, by destroying "good" bacteria alongside harmful ones, they unbalance the microbiota. In the short term, dysbiosis caused by antibiotics can result in diarrhoea14 or vaginal thrush.15 Gut dysbiosis caused by antibiotics is also suspected to have a long-term impact — particularly when antibiotics are taken during childhood — increasing the risk of various chronic diseases such as obesity and allergies.16

During infections such as viral gastroenteritis or food poisoning caused by salmonella, harmful and aggressive microbes invade the human microbiota. They come not from the microbiota itself but from outside, transmitted on hands or contaminated food, for example. These infections provoke a strong response from our immune system, with inflammation of the gut and diarrhoea. All this results in a sudden disruption to the balance of our intestinal flora. What's more, the microbes that cause these infections can also stimulate the growth of other potentially pathogenic bacteria already present in the microbiota. Infections therefore lead to dysbiosis, which all harmful bacteria take advantage of!1,12,17,18

What we eat has an impact on our microbiota throughout our lives. Any sudden changes in diet, in terms of quantity or content, can trigger dysbiosis. But it doesn't need to be sudden: while normal variations in our meals from day to day cause only temporary changes to the microbiota, the type of food we eat can cause lasting changes to the gastrointestinal ecosystem5 and ultimately become a factor in dysbiosis. Studies suggest that "Western" diets rich in fat, sugar and protein make us more susceptible to imbalances of the gut microbiota, while varied diets rich in fruit and vegetables may protect the microbiota from dysbiosis.1,19

Antibiotics

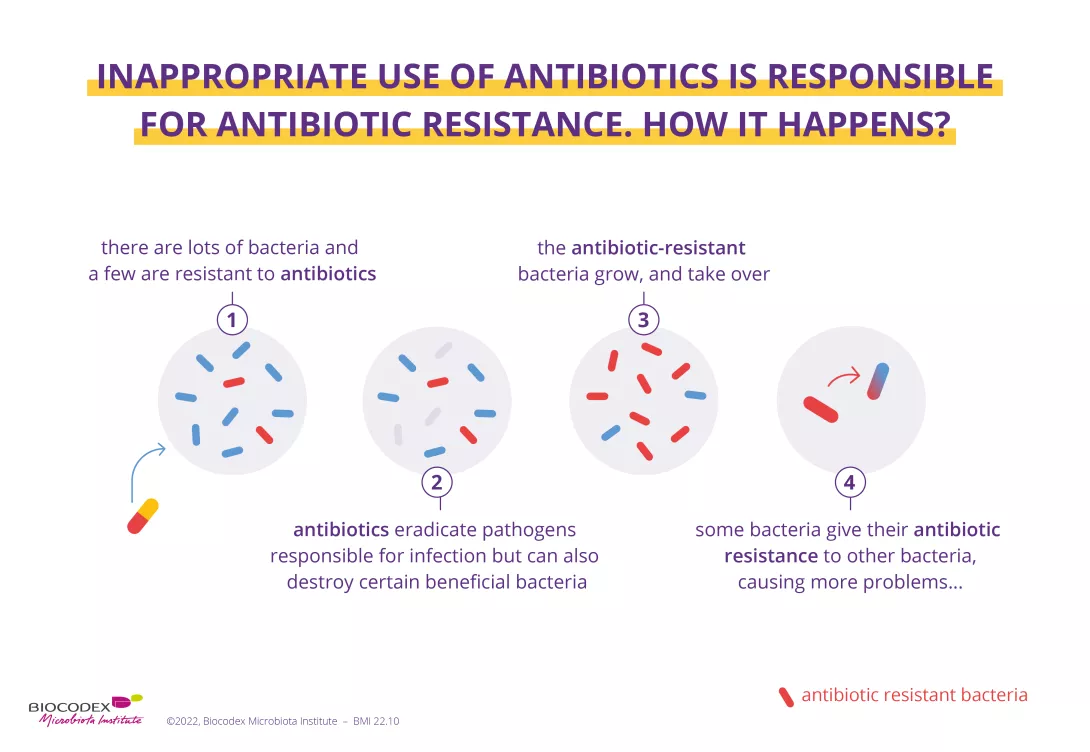

They have saved millions of lives but their excessive and inappropriate use has now raised serious concerns for health, notably with antibiotic resistance and microbiota dysbiosis. ach year, the WHO organizes the World AMR Awareness Week (WAAW) to increase awareness of antimicrobial resistance. Let’s take a look at this dedicated page:

Antibiotics: what impact on the microbiota and on our health?

Each year, since 2015, the WHO organizes the World AMR Awareness Week (WAAW), which aims to increase awareness of global antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobial resistance occurs when bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi change over time and no longer respond to medicines. As a result of drug resistance, antibiotics and other antimicrobial medicines become ineffective and infections become increasingly difficult or impossible to treat, increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness and death. Held on 18-24 November, this campaign encourages the general public, healthcare professionals and decision-makers to use antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics carefully, to prevent the further emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

Dysbiosis and diseases specific to each microbiota

Dysbiosis: a cause or a consequence of illness?

Numerous studies comparing the microbiotas of ill and healthy people have shown that dysbiosis is associated with a range of chronic conditions, including intestinal diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome and Crohn's disease, as well as obesity, allergies, asthma and certain cancers1. But is it the dysbiosis that causes the disease or the disease that causes the dysbiosis? According to scientists, the answer is still unclear, but numerous studies are currently under way to try and work it out.

In 2019, researchers launched Homo symbiosus, an extensive research project that aims to get to the bottom of this issue and give us a better understanding of why and how so many chronic diseases are associated with gut dysbiosis. The researchers' hypothesis is that "the phenomena of gut dysbiosis, microbial growth, inflammation and weakening of the intestinal wall" are mutually sustaining10.

Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is associated with a variety of diseases, including gastrointestinal, metabolic22, allergic23 and even mental24 conditions. But the human body is also home to specific microbial ecosystems located in the skin25, urinary tract26, vagina27, mouth28 and lungs29, all of which can also become unbalanced and be associated with specific diseases.

International Microbiota Observatory

How can we rebalance the microbiota?

Normally, after an episode of dysbiosis, the microbiota is able to naturally restore its initial balance (although it will never have exactly the same composition as before): it is said to be "resilient" 30. But sometimes, this "re-biosis", or return to microbial balance, can take time: even in a healthy adult, for example, it can take six months after taking antibiotics 31. Eventually, dysbiosis can lead to a prolonged state of imbalance that is self-sustaining over the long term, with the microbiota never fully returning to normal, which can be harmful to health 1 .

What should we do when dysbiosis strikes? There are several potential solutions to help us rebalance the microbiota and improve our health.

Probiotics are: "live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host".32,33 Here you will find a page dedicated to probiotics: how they work, how they are made and how to choose the right ones... Explore our page on probiotics.

Primarily derived from dietary fibre (fructo-oligosaccharides, galacto-oligosaccharides, inulin, etc.), prebiotics are indigestible nutrients or substrates that are used by the microorganisms in the microbiota and have positive effects on health.34,35 See here for more information on how they impact on the microbiota. Special products combining probiotics and prebiotics are called symbiotics.36,37

What we eat, as well as the quality and diversity of our food, affects the balance of our gut microbiota38,39, but can also impact its composition and, as a result, trigger the onset of certain diseases.22 Ask your GP and/or dietician for advice on which foods have beneficial or harmful effects, to keep your gut in the best possible shape 40 and stay healthy !

Just like other organs, the microbiota can be transplanted from one individual to another, to try and restore the balance of the recipient's microbial ecosystem.41,42 At present, this approach is well documented for the gut microbiota. It is known in this context as faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), but is only authorised for the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections.41 Intensive research is under way for other intestinal disorders.41 For the vagina, vaginal microbiota transplantation (VMT) is currently being trialled and could be a promising treatment for recurrent or refractory bacterial vaginosis 43. Studies into skin microbiota transplantation are still rare, but the initial results are promising.44,45

"Informative" -Peggy Rhinelander (From My health, my microbiota)

"Absolutely fascinating how dysbiosis reveals the hidden connections between our health and the microbiota!" -Aware Health Rewards App (From My health, my microbiota)