Insomnia in seniors: a link with the gut microbiota

While it is estimated that one in two seniors suffers from chronic insomnia, a recent study1 demonstrates a link between sleep, cognition, and the gut microbiota in elderly insomniac individuals.

Chronic insomnia and cardiometabolic disease: gut microbiota and bile acids involved?

Chronic insomnia and cardiometabolic disease: gut microbiota and bile acids involved?

Periods & vaginal microbiota: Science in progress…

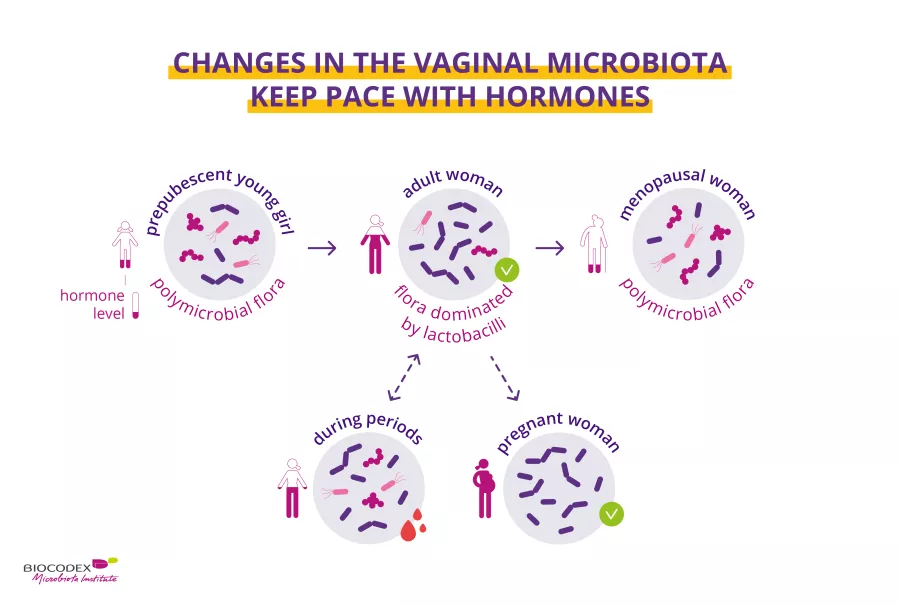

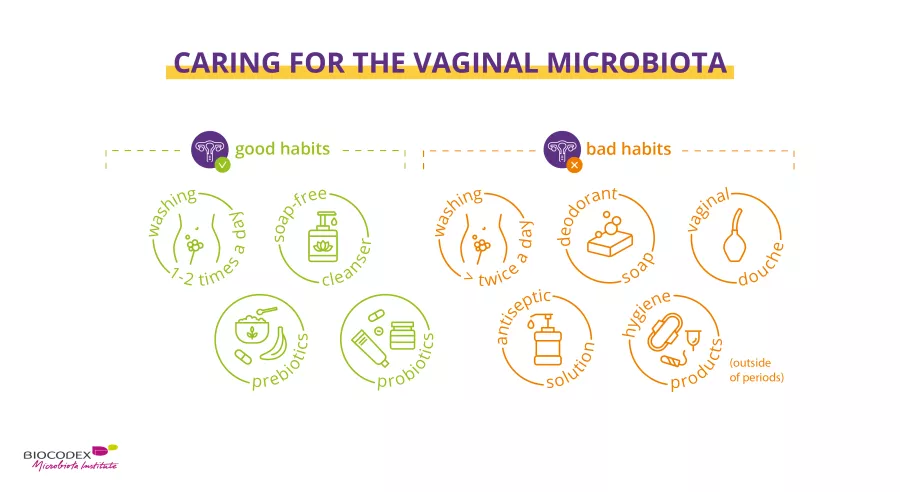

Recent scientific publications have provided new data highlighting the key role of the vaginal microbiota on women’s health. Biocodex Microbiota Institute is launching a set of expert interviews dedicated to microbiota, women and health. What do we already know about woman’s health and microbiota? What do we still have to discover?

Second act: the menstrual cycle and the vaginal microbiota. Prof. Ina Schuppe Koistinen, microbiome researcher, tells us everything!

The vaginal microbiota Vaginal yeast infection Bacterial vaginosis - vaginal microbiota imbalance The gut microbiota Diet

Endometriosis and microbiota: is there a link?

Endometriosis and microbiota: is there a link?

Urethral microbiota: a better understanding of male urinary tract infections

Urethritis is generally caused by well-known bacteria. These include gonococci, responsible for the dreaded “clap.” However, the urinary tract has its own microbiota which has yet to be explored! This is how researchers discovered1 other bacteria potentially involved in this urinary tract infection in men, which differ according to sexual orientation.

The urinary microbiota

Urinary tract infections: breaking the vicious circle

Urinary tract infections: breaking the vicious circle

Urinary tract infections: cranberries could act directly on the gut microbiota

Urinary tract infections: cranberries could act directly on the gut microbiota

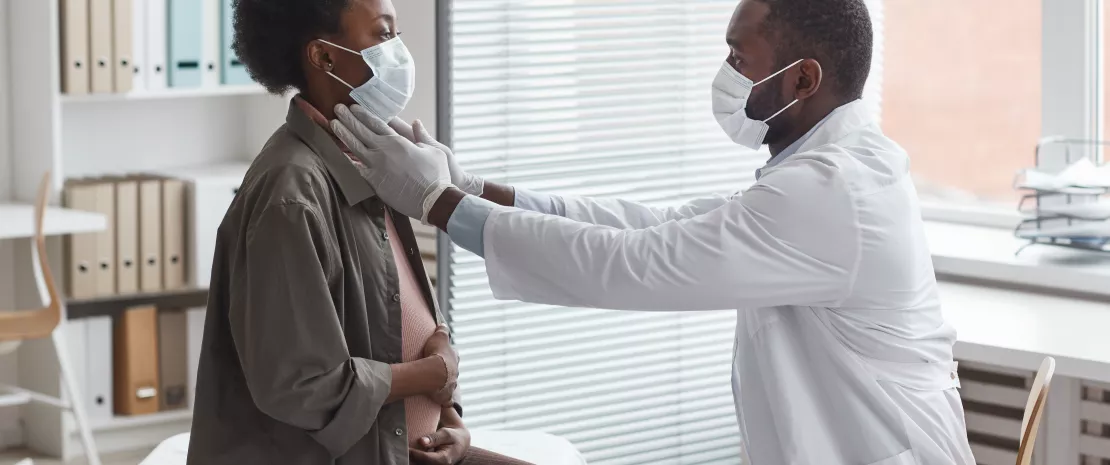

Pregnancy: is vaginal dysbiosis responsible for complications in case of COVID-19?

Contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy increases the risk of complications, all the more so if the infection is severe. A study highlights the role of vaginal dysbiosis in this relationship.

Xpeer course: The rationale behind why and how to choose a probiotic

Get free training on decision-making for choosing a probiotic from Mary Ellen Sanders, a consultant in probiotic microbiology. Delve into this course based on clinical recommendations and provide your patients with the best approach. Learn more!

Almonds: little effect on the gut microbiota

Finally, arguments supporting the health benefits of almonds will perhaps need to be revised downwards. For, against all expectations, a recent study showed that 2 snacks of almonds had little effect on the gut microbiota.

The gut microbiota

The Mediterranean diet: good for the body, good for the heart

The Mediterranean diet: good for the body, good for the heart

Almonds: limited effects on the gut microbiota

Against all expectations, the consumption of almonds seems to have no effect on the gut microbiota and intestinal transit. The only benefit observed: a rise in the level of butyrate which saves the day for the funders of the study.

Could fibers modify the microbiota?

Could fibers modify the microbiota?

Green Mediterranean diet: what links between cardiometabolic health and gut microbiota?

Green Mediterranean diet: what links between cardiometabolic health and gut microbiota?

Fat, sugar, and metabolic disease: links between the gut microbiota and immunity

We already knew that too much fat and sugar promotes obesity and type 2 diabetes. Now we also know that the gut microbiota and its immune system play a role in regulating the metabolism. Deciphering the mechanisms involved has been no small task, but researchers have recently succeeded in doing so1, revealing the major role played by excessive sugar.

The gut microbiota

When sweeteners undermine blood sugar control and disrupt the microbiota

When sweeteners undermine blood sugar control and disrupt the microbiota

The gut microbiota: a new direction for treating type 2 diabetes?

The gut microbiota: a new direction for treating type 2 diabetes?

Does the gut microbiota influence vaccine efficacy?

Some children treated with vaccines fail to develop protective immunity, especially in low- and middle-income countries. The gut microbiota is intimately linked to immune function and may be one of the factors responsible for this variability in vaccine response.