Antibiotic-associated diarrhea

Antibiotics are a powerful tool in the fight against bacterial infections. While treatments sometimes appear to be without obvious short-term side effects, the gut microbiota imbalance they provoke can cause diarrhea in up to 35% of patients.1-3 This antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) can at times cloak serious intestinal infections.3

How do antibiotics unbalance the gut flora?

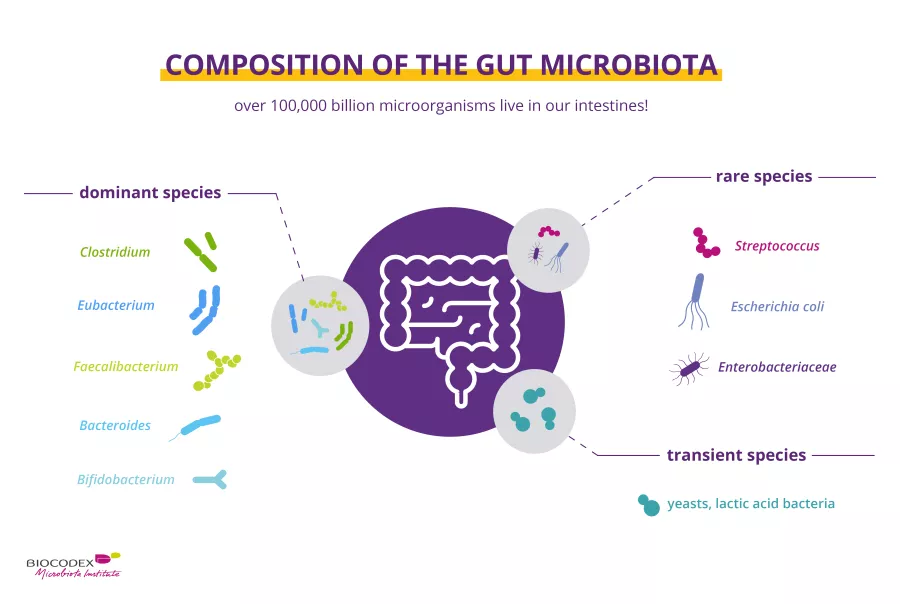

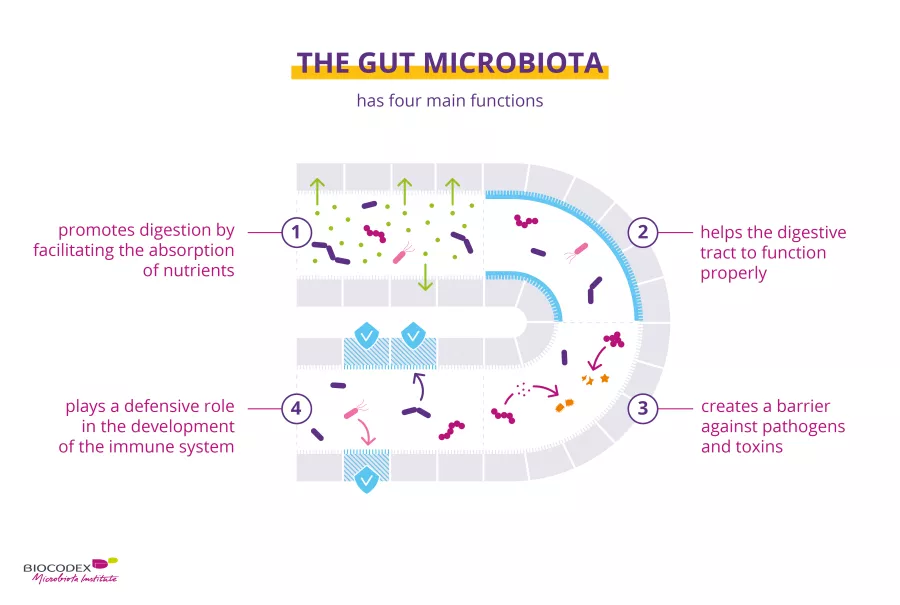

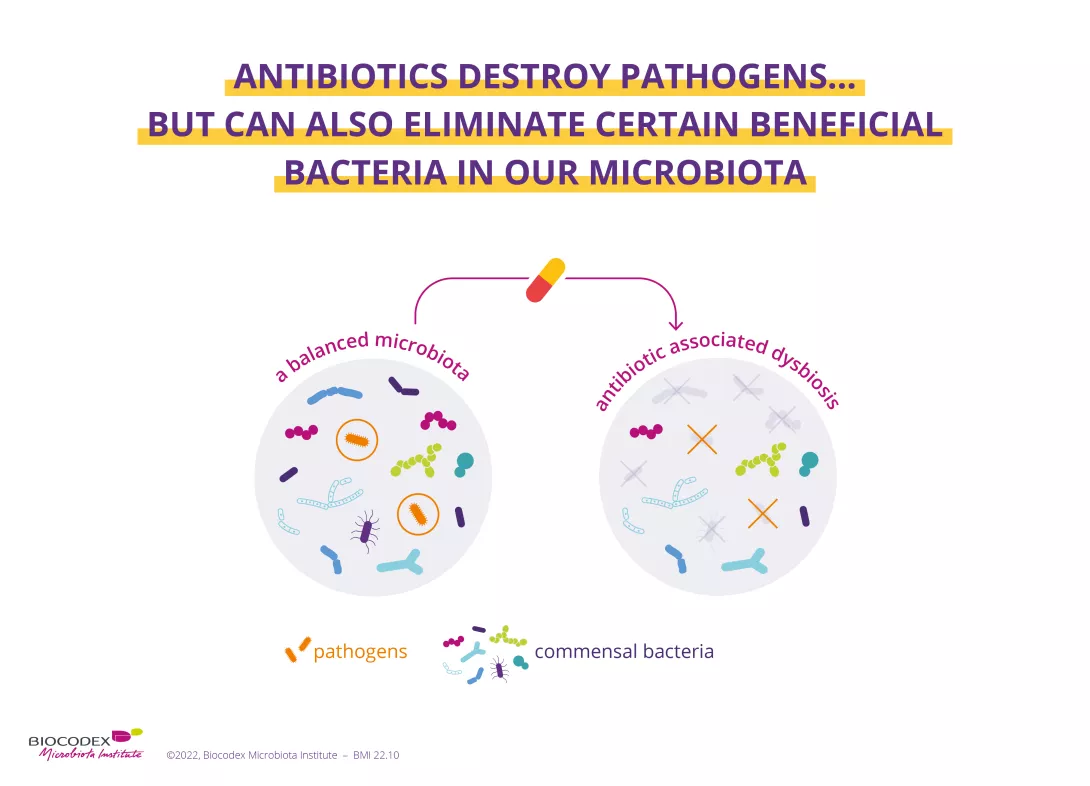

While antibiotics eradicate the (sidenote: Pathogen A pathogen is a microorganism that causes, or may cause, disease. Pirofski LA, Casadevall A. Q and A: What is a pathogen? A question that begs the point. BMC Biol. 2012 Jan 31;10:6. ) responsible for infection, they can also destroy some of the beneficial bacteria in your microbiota, systematically causing an imbalance of varying degrees in this ecosystem. This imbalance (known as (sidenote: Dysbiosis Generally defined as an alteration in the composition and function of the microbiota caused by a combination of environmental and individual-specific factors. Levy M, Kolodziejczyk AA, Thaiss CA, et al. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(4):219-232. ) ) causes AAD, as the gut microbiota is less able to perform its protective functions. AAD can affect up to 35% of patients1-3 and up to 80% of children receiving antibiotic treatment.1

Furthermore, while the gut microbiota shows a certain degree of resilience (i.e. it reverts to a composition similar to that existing before the antibiotic-induced imbalance), it does not always fully recover.4,5 Recent research has shown that antibiotics can alter the diversity and abundance of bacteria, and that this imbalance can be prolonged (usually 8-12 weeks after the end of treatment).1,6

In most cases, diarrhea without further symptoms

The main short-term consequence of antibiotic treatment is the altered bowel movements experienced by some patients, most often resulting in diarrhea. AAD is defined as three or more very loose or liquid stools within 24 hours of the beginning of antibiotic treatment or up to 2 months after its cessation.7-9 Its incidence depends on several factors, including age, context and the type of antibiotic. The diarrhea is usually mild to moderate in intensity and in the vast majority of cases is functional, i.e. associated with a gut microbiota imbalance.1 Antibiotics with the broadest spectrum of antimicrobial activity (i.e. that act on a very wide range of bacteria) are associated with higher rates of diarrhea.3

Antibiotics save life! Did you know that they also have an impact on your microbiota? Did you know that the misuse and overuse of antibiotics can lead to antibiotic resistance? Have you heard about the World AMR Awareness Week (WAAW)? All the answers in this dedicated page:

Antibiotics: what impact on the microbiota and on our health?

However, in 10%-20% of cases the diarrhea results from an infection by Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile), a bacterium that can become pathogenic due to certain factors, such as antibiotic use, being older than 65 or being affected by certain associated conditions.3 The colonization of the gut microbiota by this bacterium triggers an inflammatory reaction, with clinical consequences ranging from moderate diarrhea to much more serious symptoms, including death.3

Is ending antibiotic use the most effective treatment?

The management of AAD depends on the symptoms and the pathogen (e.g. C. difficile).10 For mild to moderate diarrhea, treatment involves ending antibiotic use (or replacing the antibiotic with one less likely to cause diarrhea) to allow the microbiota to recover and the patient to rehydrate.10

Numerous studies have shown that probiotics may help reconstitute the gut microbiota, while some probiotics have proven effective in preventing and treating AAD.6,11,12 When taken during antibiotic treatment, other probiotics have been shown to reduce the risk of primary and secondary infection with C. difficile.13-15 Lastly, fecal microbiota transplantation (naturally transferring a healthy microbiota into a sick individual in order to restore his or her microbial ecosystem) is currently only used for the most serious infections, i.e. relapses of infections with C. difficile.16,17

This article is based on scientifically approved sources but is not a substitute for medical advice. If you or your child display symptoms, please consult your family doctor or pediatrician.

What is the World AMR Awareness Week?

Each year, since 2015, the WHO organizes the World AMR Awareness Week (WAAW), which aims to increase awareness of global antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi change over time and no longer respond to medicines. As a result of drug resistance, antibiotics and other antimicrobial medicines become ineffective and infections become increasingly difficult or impossible to treat, increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness and death.

Held on 18-24 November, this campaign encourages the general public, healthcare professionals and decision-makers to use antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics carefully, to prevent the further emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

1 McFarland LV, Ozen M, Dinleyici EC et al. Comparison of pediatric and adult antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile infections. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(11):3078-3104.

2 Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2002;346:334-9.

3 Theriot CM, Young VB. Interactions Between the Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Clostridium difficile. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:445-461.

4 Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):4554-4561.

5 Francino MP. Antibiotics and the Human Gut Microbiome: Dysbioses and Accumulation of Resistances. Front Microbiol. 2016;6:1543.

6 Kabbani TA, Pallav K, Dowd SE et al. Prospective randomized controlled study on the effects of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 and amoxicillin-clavulanate or the combination on the gut microbiota of healthy volunteers. Gut Microbes. 2017;8(1):17-32.

7 Wiström J, Norrby SR, Myhre EB, et al. Frequency of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in 2462 antibiotic-treated hospitalized patients: a prospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001 Jan;47(1):43-50.

8 McFarland LV. Epidemiology, risk factors and treatments for antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Dig Dis. 1998 Sep-Oct;16(5):292-307.

9 Bartlett JG, Chang TW, Gurwith M, et al. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis due to toxin-producing clostridia. N Engl J Med. 1978 Mar 9;298(10):531-4.

10 Barbut F, Meynard JL. Managing antibiotic associated diarrhoea. BMJ. 2002 Jun 8;324(7350):1345-6.

11 Szajewska H, Kołodziej M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Saccharomyces boulardii in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Oct;42(7):793-801.

12 Hempel S, Newberry SJ, Maher AR, et al. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012 May 9;307(18):1959-69.

13 McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Greenberg RN, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in combination with standard antibiotics for Clostridium difficile disease. JAMA. 1994 Jun 22-29;271(24):1913-8.

14 Kotowska M, Albrecht P, Szajewska H. Saccharomyces boulardii in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Mar 1;21(5):583-90.

15 McFarland LV. Probiotics for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of C. difficile Infections: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. Antibiotics (Basel). 2015 Apr 13;4(2):160-78.

16 Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Apr;108(4):478-98; quiz 499.

17 Li YT, Cai HF, Wang ZH, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: long-term outcomes of faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Feb;43(4):445-57.

BMI-21.28

Antibiotics, child microbiota and long-term health effects

Antibiotics, child microbiota and long-term health effects