3 Keys to a successful consultation by Harry Sokol

Here's a quick look at Prof. Sokol best tips for a successful medical consultation

For a successful consultation:

- Avoid medical jargon as much as possible

- Use everyday life examples that can directly resonate with the patient

- Use illustrations to simplify the explanations of complex messages

Associated content

Tiny bacteria, big risks: how vaginal microbes shape pregnancy health

New research reveals a shocking twist: the tiniest shifts in vaginal bacteria during pregnancy could decide whether a harmless microbe turns deadly for newborns, reshaping what we know about protecting babies before they’re even born.

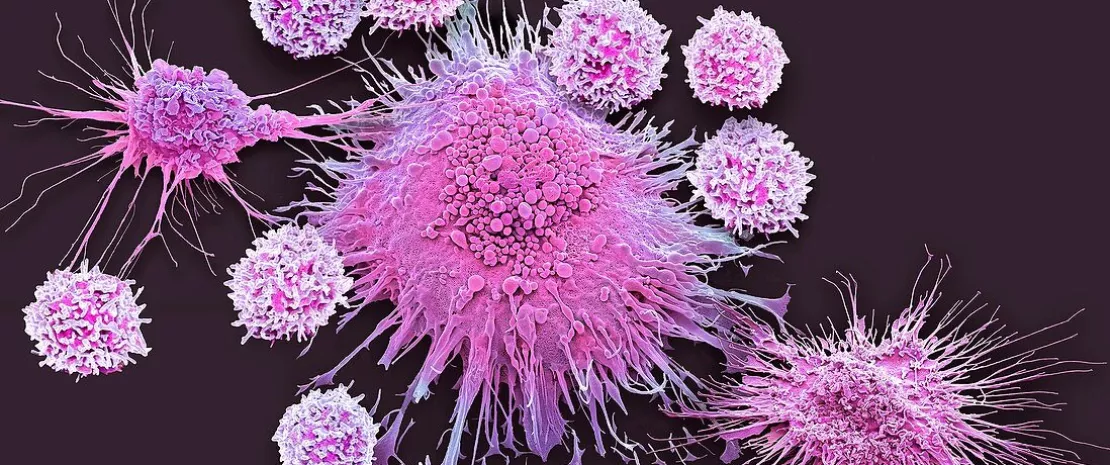

(sidenote: Group B Streptococcus (GBS) A bacterium commonly found in the gastrointestinal and vaginal tract of adults, which can cause severe infections in newborns if transmitted during delivery. ) , a bacterium quietly living in many women’s bodies, can turn deadly during pregnancy. Found in up to 40% of expectant mothers, GBS is typically harmless. But if transmitted during childbirth, it can cause life-threatening complications like sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis in newborns. Groundbreaking research 1 led by Toby Maidment at the Queensland University of Technology uncovers how the delicate balance of vaginal bacteria influences GBS’s behavior during pregnancy. The findings could change the way we think about prenatal care.

Good bacteria vs. bad news

In a study involving 93 pregnant women, researchers tracked vaginal bacteria at 24 and 36 weeks of pregnancy to see how microbial communities interact with GBS. One of the most surprising discoveries was the role of two types of bacteria: (sidenote: Lactobacillus crispatus A beneficial bacterium in the vaginal microbiota that produces lactic acid, maintaining a low pH to prevent pathogen colonization and infections. ) and (sidenote: Lactobacillus iners A less protective vaginal bacterium that produces only L-lactic acid, often associated with microbial imbalances and vulnerability to opportunistic infections ) . In women persistently colonized by GBS, L. Crispatus - a protective species that maintains vaginal acidity - was significantly reduced. Instead, L. iners, which is less effective at keeping harmful bacteria at bay, took over. This imbalance seemed to provide GBS the opportunity to stick around and thrive.

Meanwhile, women with only transient GBS colonization showed a more diverse microbial community at 24 weeks, with bacteria like Gardnerella vaginalis. By 36 weeks, this diversity declined, and L. crispatus and L. iners became dominant, correlating with the disappearance of GBS. This suggests that in some cases, the (sidenote: Vaginal microbiota The community of microorganisms residing in the vaginal environment, primarily dominated by Lactobacillus species, crucial for maintaining reproductive health. ) may naturally shift toward a healthier state - though it doesn’t always work when GBS is persistent.

What makes GBS stay or go?

Persistent GBS cases often involved the same bacterial strain sticking around through both timepoints, indicating a stable colonization. Interestingly, GBS levels in these cases dropped by about 11% as pregnancy progressed, likely due to hormonal changes that boost protective Lactobacilli. Yet, despite this decline, the persistence of L. iners continued to challenge the microbiome’s ability to fend off GBS effectively.

This study stands out because it tracked these changes over time, showing that transient and persistent GBS colonizations have distinct microbial dynamics. While L. crispatus emerges as a hero in preventing GBS, the less-effective L. iners highlights why some women remain vulnerable.

The future of prenatal care

This research opens the door to personalized interventions for GBS management. Probiotics that promote L. crispatus dominance or strategies to reduce L. iners might offer new ways to protect mothers and babies. With microbial profiling becoming more accessible, we could soon see targeted approaches to reduce GBS risks and improve neonatal outcomes.

Understanding the silent microbial battles within the vaginal microbiome is more than just scientific curiosity - it’s a matter of life and health for the most vulnerable. This study highlights how even the smallest organisms can have the biggest impact.

The vaginal microbiota

Is there a link between miscarriage and the vaginal microbiota?

Is there a link between miscarriage and the vaginal microbiota?

Does microbiota play a role in infertility?

Does microbiota play a role in infertility?

New research finds that vaginal bacteria influences Group B Streptococcus colonization during pregnancy

New research reveals how shifts in vaginal bacteria during pregnancy influence the persistence of Group B Streptococcus, a hidden but dangerous pathogen. Scientists uncover microbial imbalances that could alter approaches to prenatal care and neonatal safety.

(sidenote: Group B Streptococcus (GBS) A bacterium commonly found in the gastrointestinal and vaginal tract of adults, which can cause severe infections in newborns if transmitted during delivery. ) , a bacterium often residing silently in the human body, can become a significant threat during pregnancy. Its asymptomatic colonization in up to 40% of pregnant women can lead to neonatal complications like sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis if transmitted during delivery. New research, led by Toby Maidment from the Queensland University of Technology, explored the interplay between (sidenote: Vaginal microbiota The community of microorganisms residing in the vaginal environment, primarily dominated by Lactobacillus species, crucial for maintaining reproductive health. ) and GBS colonization over time, providing groundbreaking insights into microbial dynamics. 1

Microbial shifts and persistent colonization

Using data from 93 pregnant women, they tracked microbial changes at 24 and 36 weeks of gestation, offering new clues about persistent and transient GBS colonization. One of the standout discoveries is the contrasting role of (sidenote: Lactobacillus crispatus A beneficial bacterium in the vaginal microbiota that produces lactic acid, maintaining a low pH to prevent pathogen colonization and infections. ) and (sidenote: Lactobacillus iners A less protective vaginal bacterium that produces only L-lactic acid, often associated with microbial imbalances and vulnerability to opportunistic infections ) . In women persistently colonized by GBS, L. crispatus, a key defender against pathogens, was significantly reduced. Instead, L. iners, a species less effective in maintaining vaginal acidity and microbial balance, was more abundant. This imbalance might create an environment that allows GBS to thrive.

Interestingly, transient GBS colonization (detected only at 24 weeks) was linked to more diverse microbial communities, dominated by species like Gardnerella vaginalis. By 36 weeks, this diversity declined, and L. crispatus along with L. iners became dominant, correlating with the resolution of GBS presence. This indicates a dynamic interaction where the vaginal microbiota may naturally shift toward a protective state, though not always effectively in persistent cases.

A closer look at GBS dynamics

Persistent GBS colonization often involved the same bacterial serotype across both time points, hinting at stable colonization mechanisms. Additionally, in persistently GBS-positive women, an average 11% reduction in GBS abundance was observed as pregnancy progressed, aligning with hormonal changes that increase Lactobacilli. However, despite this decline, the presence of L. iners continued to challenge the vaginal environment's resilience.

The study’s longitudinal design—tracking changes over time rather than a single snapshot—revealed that transient and persistent colonizations differ significantly in their microbial underpinnings. It also emphasizes the importance of addressing L. iners’ role in GBS colonization, as its presence may indicate a less protective vaginal environment compared to L. crispatus or other Lactobacillus species.

Before it’s too late!

This research presents a compelling case for personalized approaches to managing GBS in pregnancy. While L. crispatus emerges as a key player in vaginal health, L. iners seems less capable of offering protection against opportunistic pathogens. Understanding these dynamics could pave the way for interventions, such as probiotics targeted at increasing L. crispatus dominance or other strategies to bolster vaginal defenses.

Moving forward, microbial profiling may become a cornerstone of personalized obstetric strategies, potentially reducing the risks associated with GBS and improving neonatal outcomes.

Mother-fetus interaction via the gut microbiota has been discovered

Mother-fetus interaction via the gut microbiota has been discovered

Female anatomy, microbiotas and intimate hygiene

The difference between vulva and vagina? (You don't get it ?). Intimate hygiene? (Still don't get it?)... When you ask women about these subjects, they’re often evasive. Practical lesson in anatomy and good practices.

We thought the younger generations had been successfully liberated by the feminist struggles of the 2000s, but they are proving even less comfortable than their elders when talking about female genitalia. And while forty-somethings scramble for intimate deodorants, under the influence of adverts promoting the freshness of their nether regions, the next generation, more mindful of their image, are turning to cosmetic procedures, like (sidenote: Vulvoplasty Plastic surgery of the vulva, to increase or reduce the size or volume of the labia majora. ) 1. Each generation has its own unique relationship with intimacy, it would seem. Regardless, the hygiene and health of this fragile body area should concern us at all ages... hence these few cheeky reminders, to lift the veil on any taboos.

A little Anatomy

The female genitalia is both a terra incognita in terms of anatomy and a taboo in terms of conversation, including among women. So much so that health professionals struggle to understand their patients’ ailments due to insufficiently clear explanations, and/or because they confuse the vulva (external part of their genitalia) with their vagina (internal part)1.

In short:

the vulva is on the outside and the vagina within!

The vulva

is made up of a set of tissues visible on external examination1:

- part of the pubic mound (also called mons pubis or mons Venus), which is the fleshy, hairy area covering the pubic bone,

- the clitoris, linked to sexual pleasure, which is the female counterpart of the male foreskin,

- the labia majora, which are the larger protective outer folds,

- the labia minora, which are located inside the labia majora and comprise numerous sebaceous glands,

- and the vulval vestibule, which is the area between the labia minora, where the vaginal entrance is found, and the urethral meatus, just above it (orifice of the urinary system).

The skin covering the pubic mound and labia majora has sebaceous glands1 that produce a protective hydrolipidic film1,2.

The vulva also has glands (Bartholin’s glands, Skene’s glands) that lubricate the labia minora and vulval vestibule during intercourse1.

The vagina

is a cavity about ten centimeters in length that is not visible from the outside.

- At its lower part, it communicates with the exterior, at the vulva, or more specifically the vulval vestibule;

- at its apex, it leads to the cervix1.

The vagina can accommodate tampons and menstrual cups during menstruation, a partner’s penis during intercourse, your favorite sex toy... and your gynecologist’s speculum at medical consultations!

Now that we’ve come this far, we might as well explain all the other orifices. From front to back, the female genitals include three openings, in this order:

- the urinary meatus, connected to the bladder (which stores urine) by a canal called the urethra (which allows urine to be evacuated outside the body during urination)2,

- then the entrance to the vagina (reproduction)

- then the anus (stools).

We speak also of:

designating the area surrounding the anus;

designating the large area formed by the vulva and the perianal area (in other words, the entire crotch area).1

Female intimate microbiotas

Our intimacy is no exception; like other organs, it is home to several microbiotas, which are:

Let’s start with the vulvar microbiota. You’d think we know it well, given that it’s on the outside. And yet, data on this subject is scarce1,3. The few studies carried out pay lip service to the possible presence of various bacteria (Lactobacillus, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus and Prevotella) and yeast-like fungi1,3.

It can clearly be a matter of vulvar microbiotas in the plural, depending on the area of the vulva: microbiota of the pubic mound, microbiota of the labia majora, microbiota of the labia minora, etc...3

One thing seems certain, however, diversity is the name of the game, not only:

- in each woman’s vulvar microbiota, where an abundance of (sidenote: Microorganisms Living organisms too small to see with the naked eye. This includes bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea, protozoa, etc., collectively known as ’microbes’. Source: What is microbiology? Microbiology Society. ) coexist, but also

- between two women (no single listed species is found in all women)1.

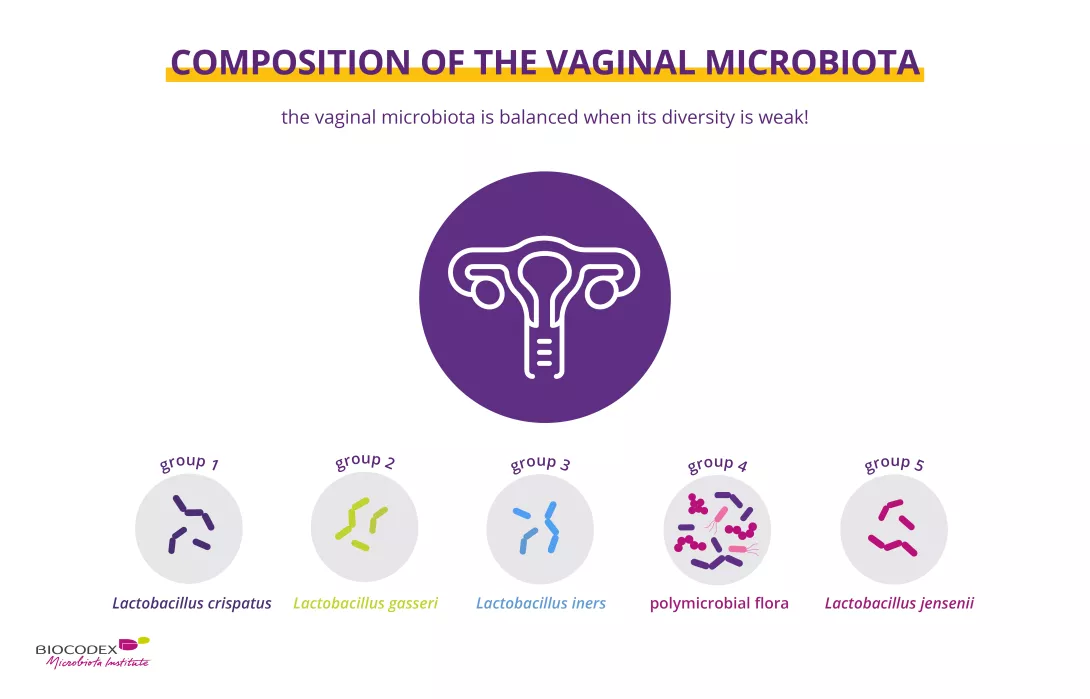

When it comes to the vaginal microbiota (or vaginal flora), the opposite is true. In the vagina, lactobacilli (in particular Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus iners, Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus jensenii) generally reign supreme and maintain local acidity by producing lactic acid1,4.

This acidic pH, from 4.0 to 4.5, keeps (sidenote: Pathogens A pathogen is a microorganism that causes, or may cause, disease. Pirofski LA, Casadevall A. Q and A: What is a pathogen? A question that begs the point. BMC Biol. 2012 Jan 31;10:6. ) at bay, as do the hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins produced by these same lactobacilli to overcome the most recalcitrant pathogens.

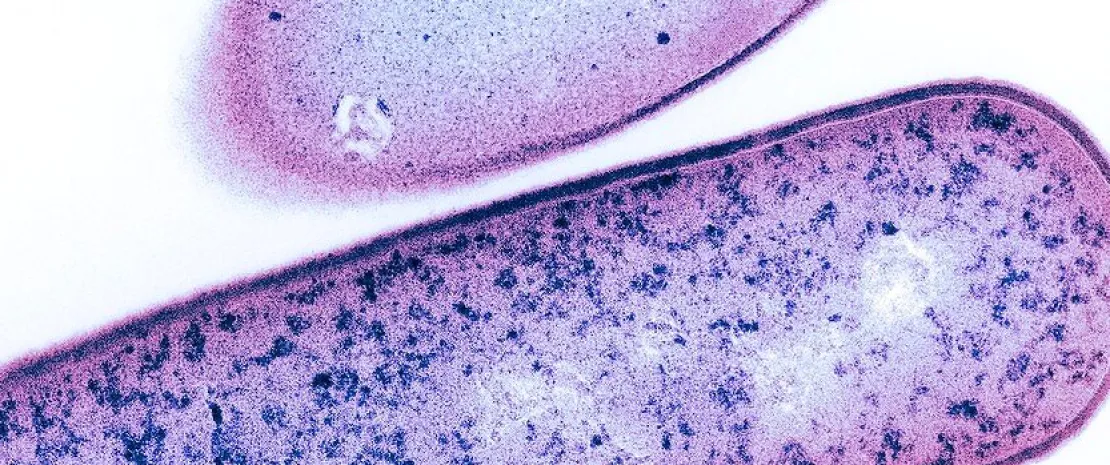

Representation of the main bacterial groups in the vaginal microbiota, including lactobacilli, which are key to intimate balance and infection prevention.

The urinary microbiota has long been considered sterile. This is a mistake, since urine contained in the bladder also has a microbial ecosystem. Although the urinary microbiota is quite distinct from its close neighbors (anal, vaginal and vulvar microbiotas), it shares certain microorganisms with them5. It is also much less densely populated, and often dominated by a single bacterial type. These include mainly lactobacilli, but also Gardnerella, Streptococcus and Corynebacterium6.

Finally, the perianal microbiota is a reflection of our very rich gut microbiota, particularly in the colon: when we pass stools, intestinal bacteria come into contact with this area and can take up residence there1.

1 in 5 Only 22% of women claim to know exactly what the “vaginal microbiota” is (+2 points vs. 2023).

Microbiotas so close as to be exchanged

Vulvar, vaginal and perianal microbiotas evolve over time. For example, the vaginal microbiota is influenced by age, sex hormones and external factors such as pollution, stress, antibiotics, etc4. Imbalances can occur: after menopause, the drop in estrogen leads to a loss of lactobacilli and therefore a rise in pH, resulting in frequent vaginal dysbiosis7. As for the anal microbiota, it depends above all on diet and stress: excessive anxiety induces an inflammatory response that favors the development of pathogenic bacteria in the digestive tract... which end up in the perianal area1.

The proximity of the urinary, vaginal and anal orifices also explains possible “exchanges” of flora between the 3 microbiotas in these 3 areas... and the possible invasion of the vaginal microbiota by digestive Escherichia coli that may have ventured beyond the perianal area1.

Bacterial Vaginosis

Antibiotics

Excessive hygiene, over-waxing, too-tight clothing… a losing combo

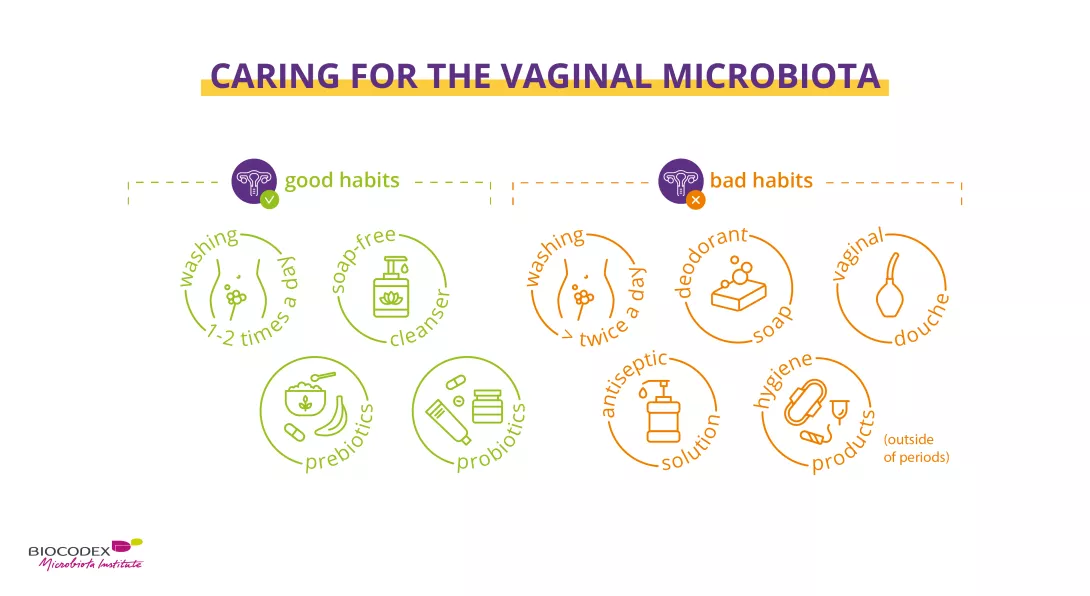

Paradoxically, inappropriate intimate hygiene practices can actually encourage exchange and imbalance. Washing the vulva too aggressively (with unsuitable products) or too frequently (more than once a day) can quickly damage the skin barrier function in this very fragile and reactive area. Water alone can be enough to dry it out and expose it to itching and burning8. And the perfumed soaps, intimate sprays, lubricants, deodorants, etc. that some women self-prescribe in an attempt to treat odors, itching, pain and dryness are counterproductive4.

Also to be avoided:

Products not intended for intimate hygiene (hand sanitizers, baby wipes, oils, shaving cream and body lotions). More women than you might think use them differently from their intended purpose: 41.6% of women in one study admitted using baby wipes for vulval cleansing... and 2.1% for internal vaginal cleansing4!

Let’s not forget:

the vagina has no need to be cleansed!

Another common error: waxing or shaving the entire vulva1,9. This is a fashion phenomenon that concerns 84% of premenopausal American women, for 2/3 of whom it is a daily or weekly routine. Often justified on hygienic grounds, the reverse is actually true: it creates lesions that make it easier for bacteria and viruses to enter. Alterations in the vaginal microbiota have in fact been observed in women opting for full vulva hair removal9.

Finally, wearing very tight, synthetic clothing seems also to encourage the development of pathogens (a warmer, more humid environment), resulting in more frequent itching and urogenital problems1.

Best practices for preserving the vaginal microbiota: gentle intimate hygiene, prebiotics, and probiotics – as opposed to vaginal douching, harsh soaps, and antiseptic solutions.

Better informing women

1 in 2 52% of women surveyed said they had never received information on proper intimate hygiene practices, and 25% said they had only been informed once by their health practitioner.

Why is there such a gap between practices and recommendations? There are undoubtedly many reasons for this:

- too few women are informed by their doctors about good practices: 52% of women surveyed said they had never received such information, and 25% had only been informed on one occasion by their health practitioner17;

- the frequent confusion between vulva and vagina means messages are misunderstood;

- the stupidest myths are often those that stick most1.

This problem is all the more important when you consider that the vulva is the first line of defense in a woman’s genital system10.

What women know (and don't know) about their vaginal microbiota

(Real!) good hygiene practices

The right way to preserve the microbiota and the delicate protective hydrolipidic film of female genitalia. A routine that respects the balance of the vulva, with products adapted to the age and specific needs of each woman.

In all cases, there are 3 main immutable principles10:

- external washing only (= vulva, no vaginal douching), from front to back (vulva then anus)

- without a washcloth (which may contain bacteria), but with clean hands,

- once a day. Only women suffering from frequent diarrhea can justify more frequent external washing (due to more frequent bowel movements). Or during menstruation, when you may need to wash the intimate area a second time during the day.

Washing with water alone can dry out the skin and aggravate itching10. It’s best to use a mild, soap-free cleanser that respects the vulvar microenvironment and maintains the balance of its microbiota1. And that’s all. You can be absolutely sure that less is more on this delicate part of the body.

Finally, here are a few additional recommendations to help you adopt the right practices throughout the day10:

- at night, avoid wearing underwear;

- when you get out of the shower (preferable to a bath), dry yourself thoroughly with your own towel, without rubbing but gently dabbing your crotch area;

- when dressing, opt for cotton rather than synthetic undergarments, avoid regular use of panty liners, prefer loose-fitting clothes, replace tights with stockings if possible;

- when using the toilet, wipe from front to back (to avoid bringing anal bacteria to the vulva) with unscented and ideally uncolored paper;

- Here too, it is important to respect the main principles of intimate hygiene: external washing only; with your hands; once a day10.

- after sexual relations (protected!, unless you’re sure your partner isn’t carrying an STI), take time to urinate if you’re prone to cystitis;

- during menstruation, do not use scented sanitary pads, and change your sanitary pad or tampon regularly10.

Probiotics and prebiotics

Healthy vaginal microbiota depends on good intimate hygiene. But sometimes that’s not enough, and a little help may be needed to boost the good bacteria in your microbiota, with:

Probiotics

Probiotics, living microorganisms which, when administered in appropriate quantities, have beneficial effects on the host’s health11,12. Administered orally or vaginally, they can help restore vaginal flora, improve symptoms and reduce the risk of various vaginal infections recurring, form puberty to menopause13.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics, non-digestible dietary fibers with positive health effects used selectively by beneficial microorganisms in the host microbiota12, 14. In other words, the preferred foods of probiotics to help them thrive. For example, female prebiotics boost vaginal lactobacilli and help normalize vaginal acidity15,16.

What is the difference between prebiotics, probiotics and postbiotics?

To sum up...

Female genitalia are made up of:

- the vulva (external part)

- and the vagina (the cavity that connects the vulva to the uterus, into which you can insert a tampon when you have your period).

The genitalia are home to several microbiotas: the vulvar microbiota in which diversity is key, the vaginal microbiota dominated largely by lactobacilli, the urinary microbiota which is sparsely populated (for a long time, urine was wrongly thought to be sterile), and a very rich perianal microbiota (contact with stools).

The proximity of the urinary, vaginal and anal orifices explains why “exchange” of flora between the microbiotas of these areas is possible, particularly in the case of inappropriate intimate hygiene: too aggressive washing, waxing or shaving of the entire area, wearing clothes that are too tight, etc.

Due to a lack of information, many women do not adopt the right practices to protect their microbiotas. But it’s not too late – so bite the bullet and talk about it with your doctor!

If your vaginal microbiota is flagging, prebiotics and probiotics can help you restore a balanced vaginal flora.

2. Biology of the Kidneys and Urinary Tract. MSD Manuel. https://www.msdmanuals.com/home/kidney-and-urinary-tract-disorders/biology-of-the-kidneys-and-urinary-tract

6. Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ, Brubaker L. Female urinary microbiota. Curr Opin Urol. 2017 May;27(3):282-286.

7. Auriemma RS, Scairati R, Del Vecchio G et al. The Vaginal Microbiome: A Long Urogenital Colonization Throughout Woman Life. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 Jul 6;11:686167.

Lactobacilli still beneficial after menopause

After menopause, Lactobacillus dominance and low alpha diversity are associated with less vaginal inflammation, as previously reported in pre-menopausal women. Thus, despite their reduced presence, Lactobacilli seem to continue to have beneficial effects.

We know that in pre-menopausal women, increased diversity in the vaginal microbiota and a loss of Lactobacillus dominance are associated with greater mucosal inflammation. This leads to a higher risk of dysplasia and cervical infection.

Does this link between vaginal microbiota and inflammation continue after menopause? The post-menopausal period remains poorly understood, even if we know that the vaginal microbiota tends to become more diversified and less dominated by lactobacilli once the reproductive period is over.

A US study 1 on 119 post-menopausal women (average age 61 at inclusion) seeking treatment for moderate to severe vulvovaginal discomfort (irritation, dryness, etc.) sought to answer this question.

119 post-menopausal women

The subjects were divided into three groups based on the treatment received and were followed for twelve weeks. The three treatments were as follows:

- estradiol tablet and placebo moisturizing gel

- placebo tablet and moisturizing gel

- double placebo

At baseline, 29.5% of participants had their vaginal microbiota dominated by lactobacilli.

Caucasian women were less likely to have this protective flora. Overall, lower Lactobacillus dominance and lower alpha diversity in vaginal fluids were associated with lower concentrations of inflammatory immune markers, while complete loss of Lactobacillus dominance was associated with higher concentrations of pro-inflammatory (sidenote: Cytokine A small protein involved in communication between cells, especially in the immune system. Cytokines: Introduction_British Society for Immunology ) , as observed in previous studies on post-menopausal women.

21 years Globally, a woman aged 60 years in 2019 could expect to live on average another 21 years.

26% The global population of post-menopausal women is growing. In 2021, women aged 50 and over accounted for 26% of all women and girls globally. This was up from 22% 10 years earlier.

Lasting support from lactobacilli

This mirrors the tendency reported in women of childbearing age. Lactobacilli may thus continue to play a protective role after menopause, with beneficial effects on the immunity of the vaginal mucosa by helping to reduce inflammation – or at the very least, by being associated with this decrease.

Conversely, an increase in the alpha diversity of the vaginal microbiota is thought to be associated with pro-inflammatory cytokines.

These results imply that low diversity and high lactobacilli dominance remain beneficial to vaginal health. While Lactobacillus dominance may not be “normal” after menopause, it could represent a favorable microenvironment associated with a lower inflammatory status.

Premenopause and depression: towards a new management pathway?

Premenopause and depression: towards a new management pathway?

Postmenopause: the beneficial action of estradiol on the vaginal microbiota

Postmenopause: the beneficial action of estradiol on the vaginal microbiota

Oral microbiota transplantation: a ray of hope for preventing chemotherapy-induced mucositis?

A pilot study 1 on a female infant with neuroblastoma shows that transplantation of the mother’s oral microbiota could effectively prevent chemotherapy-induced mucositis.

(sidenote: Oral mucositis Acute, painful inflammation of the oral mucosa, often induced by anti-cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Symptoms include redness, pain, and ulceration, and can be accompanied by dry mouth, altered taste, and difficulty in eating. It can lead to malnutrition, dehydration, and reduced quality of life. Treatment is symptomatic and aims at relieving pain, promoting healing, and preventing infection. Explore Cleveland Clinic ) is a common side-effect of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. It is characterized by inflammation of the oral and intestinal mucosa.

The result is lower quality of life for patients, poorer compliance with treatment, feeding difficulties, and complications that are all the more serious when the patient is frail. Since current therapies only treat symptoms, modulating the oral microbiota seems to be a promising new approach.

Following on from work suggesting a link between oral microbiota and the development of chemotherapy-induced mucositis, the publication at the end of 2024 of a pediatric clinical case has increased our hopes.

Oral mucositis is diagnosed in more than 70% of patients after hematopoietic cell transplantation and in 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy at standard doses.

Decision and transplantation protocol

The story relates to a six-month-old Russian girl, diagnosed at the age of four months as suffering from a retroperitoneal neuroblastoma with multiple metastases. Chemotherapy was rapidly complicated by various side effects, including severe oral mucositis, rapid weight loss, and C. difficile infection.

The doctors decided to perform a transplant of the healthy 33-year-old mother’s oral microbiota. The donation samples were spread out over the day (nine samples of 1.5 mL), away from meals and tooth brushing.

Oral microbiota and chronic conditions

Oral transplantation

During each of the following three cycles of chemotherapy (the dosage of which was reduced), the infant received her mother’s saliva in her mouth (13.5 mL per day for 10 days) some thirty minutes after breast-feeding.

After six chemotherapy cycles, the patient underwent a complete resection of a retroperitoneal tumor along with right-sided adrenalectomy, followed by high-dose chemotherapy with subsequent autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT). A final oral transplant of maternal saliva was performed prior to the auto-HCT.

Effects on mucositis

Oral microbiota transplantation effectively prevented the development of mucositis following three new cycles of chemotherapy, and only grade 1 oral mucositis developed after auto-HCT. In all parts of the mouth, there was a decreased abundance of bacteria from the Staphyloccaceae, Micrococcaceae, and Xanthomonadaceae families. Conversely, there was an increase in the relative abundance of Streptococcaceae and certain other bacterial taxa.

Maternal saliva transplantation thus appears to have prevented further severe mucositis in the patient, and to have been accompanied by a change in oral microbiota composition. No adverse events due to the transplantation of maternal saliva were noted.

Although it is only one case, the pilot clinical study described here paves the way for possible oral microbiota transplants to reduce the risk of mucositis during chemotherapy. At the very least, it highlights the possibility, safety, and efficacy of transplanting oral microbiota from a healthy donor to a neuroblastoma patient to prevent chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis.

Antibiotics disrupt cancer immunotherapy via gut and immune effects

Antibiotics disrupt cancer immunotherapy via gut and immune effects

Vaginal lactobacilli's anti-inflammatory superpowers

What if the secret to controlling vaginal inflammation lies within the microbiome? New research reveals Lactobacillus crispatus produces β-carboline compounds that selectively suppress inflammation while preserving immunity, opening doors to novel therapies.

A healthy vaginal microbiome, typically dominated by (sidenote: Lactobacillus A group of beneficial bacteria commonly found in the vaginal microbiome. They produce lactic acid, helping maintain a low pH to protect against infections. ) species, is central to gynecological health. Yet, the mechanisms through which these microbes modulate inflammation have long eluded researchers. A new study 1 led by Virginia J. Glick, published in Cell Host & Microbe, unveils that certain strains of Lactobacillus crispatus produce β-carboline alkaloids - small molecules that exhibit targeted anti-inflammatory properties.

This discovery offers a fresh perspective on how these bacteria contribute to immune homeostasis and sets the stage for potential therapeutic applications.

77% BC6 perlolyrine cut inflammatory signals by 77% and restored immune cell activity to normal.

β-carbolines: Precision immunomodulators

The study identified β-carboline compounds, including (sidenote: Perlolyrine (BC6) A potent β-carboline compound identified in Lactobacillus crispatus that reduces inflammation while preserving immune defense. ) , as potent suppressors of inflammatory signaling. Using a dual reporter system in human monocyte-derived THP1 cells, researchers demonstrated that L. crispatus-derived β-carbolines inhibited NF-kB and type I (sidenote: Interferon (IFN) Signaling A key immune pathway that fights infections but can drive inflammation when overactive. ) (IFNAR) pathways. These molecules uniquely suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokine production in immune cells while leaving antiviral responses intact in epithelial and barrier cells - a level of selectivity rare among anti-inflammatory agents.

Notably, this is the first time that β-carboline, previously linked to plants and soil microbes, have been identified as products of vaginal Lactobacillus strains. Their discovery highlights a new dimension in microbiota-host interactions. Furthermore, cervicovaginal lavage samples from individuals with healthy vaginal microbiomes (low (sidenote: Nugent score A diagnostic scoring system used to assess bacterial vaginosis based on the presence and proportions of certain bacteria in a Gram-stained vaginal sample. ) ) were significantly enriched with β-carboline compared to those with (sidenote: Bacterial vaginosis Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a type of vaginal inflammation caused by an imbalance of the bacterial species that are normally present in the vagina. ) (high Nugent scores), underscoring their potential as biomarkers for microbiome health.

New insights into vaginal microbiome dynamics: a game changer for women’s health

Translating science into therapeutics

To explore the clinical relevance of these compounds, researchers applied BC6 topically in a mouse model of vaginal inflammation induced by herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2). The results were striking:

- BC6 significantly reduced inflammation

- Dampened pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and IL-18

- And improved disease scores without affecting viral titers

The treatment maintained innate immune cell populations while decreasing the inflammatory signaling driving tissue damage.

Even more intriguing, some mice pre-treated with L. crispatus supernatant remained asymptomatic despite similar viral burdens as untreated controls. This suggests a role for these compounds in enhancing disease tolerance - a concept gaining traction in immunological research.

What this means for clinical practice?

The findings offer several critical insights. First, the study highlights the functional role of Lactobacillus crispatus in immune modulation, moving beyond its lactic acid production. Second, the specificity of β-carboline to suppress inflammatory pathways in immune cells without impairing barrier defenses provides a targeted approach to managing vaginal inflammation.

This research also paves the way for microbiome-based therapies, particularly in treating inflammatory disorders like bacterial vaginosis and vaginitis. Topical applications of β-carboline, such as perlolyrine, could offer a natural, precise alternative to broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory drugs, minimizing side effects and preserving immune functions.

Menstrual toxic shock syndrome: balanced flora protects against attacks by S. aureus

Menstrual toxic shock syndrome: balanced flora protects against attacks by S. aureus

Bacterial vaginosis: sexual transmission & genomic insights

Bacterial vaginosis: sexual transmission & genomic insights

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR): The Biocodex Microbiota Institute steps in to tackle a silent health crisis

The Biocodex Microbiota Institute is a leader in scientific information and a key player in educating and training healthcare professionals and the general public on the importance of human microbiota. From November 18 to 24, for the fifth year running, the Institute is taking part in World Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Week (WAAW), organized by the WHO. For the 2024 edition, experts from the Biocodex Microbiota Institute will create the first “Antibiotic Resistance Awareness Mural”. The aim is to present the issues and challenges associated with antibiotic resistance in a fun, collaborative way in the hope of changing patient behavior.

A global week to raise awareness of the dangers of antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most serious threats to public health worldwide. According to the WHO, unless urgent measures are taken, this scourge could cause more than ten million deaths a year by 2050.

Although with proper use, antibiotics remain a major medical advance, their abuse and misuse contribute to antibiotic resistance by encouraging the emergence of resistant bacteria, which puts at risk. Despite this, only 31% of the French public says it is aware of the negative impact of antibiotics on the microbiota, according to the International Microbiota Observatory, a survey conducted in 2024 by Ipsos for the Biocodex Microbiota Institute. For the second year running, the Biocodex Microbiota Institute has commissioned Ipsos to carry out a major international survey on 7,500 individuals across 11 countries in order to better understand people’s level of knowledge and behaviors when it comes to their microbiota.

Against this worrying backdrop, World AMR Awareness Week represents a crucial opportunity to raise awareness among the public and healthcare professionals about the importance of proper antibiotic use.

Antimicrobial resistance awareness mural to get the message across to patients

Over the past five years, the Biocodex Microbiota Institute has played an active role in this global awareness campaign, with multiple initiatives to promote the proper use of antibiotics and raise awareness among the general public and healthcare professionals of their impact on microbiota. For the 2024 edition, teams from the Biocodex Microbiota Institute worked alongside Querceo to create the first “antibiotic resistance awareness mural.”

“We went for an original, fun, and collaborative format to raise awareness among a wide audience, from patients and healthcare professionals to Biocodex employees. The aim of this mural is clear: to involve as many people as possible in raising awareness about antibiotic resistance. By combining card games, quizzes and, above all, collective knowledge about the solutions to be implemented, this first-of-its-kind mural aims to popularize the issues surrounding antibiotic resistance, all while illustrating the central role of microbiota in human health.”

Training 1,700 “Biocodex Mural Makers” to animate a first-rate community of ambassadors

The campaign kicked off on November 14 with a scientific conference entitled “Antibiotic resistance: microbiota at the heart of a silent pandemic”, featuring, among others, Vanessa Carter, survivor of antibiotic resistance and member of the WHO working group on antibiotic resistance, and Professor Etienne Ruppé, specialist in antibiotic resistance and bacteriologist at the Bichat-Claude Bernard hospital in Paris.

As part of this awareness-raising week, Biocodex is also mobilizing its 1,700 employees for the initiative. Participative workshops will be organized throughout the week of November 18 to 24 to train employees on how to design the antibiotic resistance awareness mural. These workshops provide an opportunity for exchange and co-creation, to reinforce collective awareness about the proper use of antibiotics.

For Catherine Perret, Chief People Officer at Biocodex, “training our 1,700 employees on how to design this mural reinforces their commitment to raising awareness about antibiotic resistance. This makes them active ambassadors for the cause, helping to spread the importance of the proper use of antibiotics.”

About the Biocodex Microbiota Institute

The Biocodex Microbiota Institute is an international knowledge hub dedicated to human microbiota. The Institute communicates with its users in seven languages, targeting both healthcare professionals and the general public with the aim of raising awareness about the vital role this organ plays in our health. The Biocodex Microbiota Institute’s primary mission is educational: to spread the word about the importance of microbiota for everyone.

About Querceo

Querceo is a consulting firm that takes a collaborative and systemic approach to supporting organizations through the ecological transition. By creating and disseminating awareness-raising workshops, such as the Biodiversity Mural, the One Health Mural, or the SiNergie workshop, Querceo helps mobilize organizations, enabling each individual to understand and take ownership of the major challenges of tomorrow.

Transgender women: a specific neovaginal flora

A transgender or trans person is someone whose gender assigned at birth does not align with how they feel. Not all transgender women choose to undergo surgery, but researchers 1 have studied the vaginal flora of those who have had an operation to create a neovagina. A well-balanced neovaginal microbiota is crucial for the good health of transgender women who receive surgery. Allow us to explain…

The vaginal microbiota The skin microbiota Women disorders

Some (sidenote: Transgender A person whose gender identity, i.e. their intimate and personal experience of their gender, differs from the sex assigned to them at birth. WHO, MSD Manual, Government of Canada ) women correct the (sidenote: Gender incongruence Marked and persistent incongruence between an individual’s experienced gender and assigned sex, which often leads to a desire to ‘transition’ through hormonal treatment, surgery or other health care services. WHO, MSD Manual, Government of Canada ) of feeling like a woman in the depth of their being despite the physical presence of male genitalia and being referred to as a man by undergoing “penile inversion vaginoplasty.” In other words, by surgically transforming their penis into a vagina. However successful the surgery, the skin of this newly constructed vagina will combine skin from the penis and a skin graft from the (sidenote: Scrotum Skin that protects the testicles in men WHO ) and/or other area(s) (stomach, groin, etc.).

0.1% to 1.1% An estimated 0.1% to 1.1% of the world’s population are transgender people. ²

Twice Breast surgery is twice as frequent (8-25%) as genital surgery (4-13%). ³

How does this affect health? Vaginal microbiota makes a crucial contribution to good vaginal health in (sidenote: Cisgender A person whose gender identity aligns with the sex assigned to them at birth. WHO, MSD Manual, Government of Canada ) women. And American researchers have now turned their attention to the intimate flora of transgender women undergoing surgery: might the composition of neovaginal microbiota explain certain problems, including the frequently reported issue of vaginal discharge?

Cisgender vs. transgender vaginal microbiota: what are the differences?

It is a question worth asking, and one that has now been answered thanks to a study comparing the vaginal microbiota of transgender women undergoing vaginoplasty with that of cisgender women. The results? They have very different microbiota.

1 trangender man in 2

Gender reassignment (confirmation) surgery is more common in transgender men (42 to 54%) than transgender women (28%). 3

The vaginal flora of cisgender women is not very diverse and is dominated largely by lactobacilli, which creates an acidic environment that repels pathogens. That of transgender women has less than 3% of these precious allies and is much more diverse. Diversity in the vagina is not a sign of good health; quite the opposite. It is observed in cisgender women suffering from bacterial vaginosis, which increases risk of sexually transmitted infections (including HIV/AIDS) and miscarriage.

How is this new microbial ecosystem created?

Or more precisely, which bacteria make up the neovaginal microbiota of transgender women having undergone surgery? They result no doubt from the flora of the skin (penis, scrotum, etc.) used during surgery. However, oral-genital and genital-genital transmission also appear to be involved.

In fact, the neovaginal flora of transgender women having undergone surgery has been shown to include bacterial species typical not only of the skin and digestive tract, but also of the mouth. Since sexual relations influence the likelihood of a bacterium called E. faecalis, there is also genital transfer.

“Gender identity disorder”?

In May 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) removed “gender identity disorder” from its official diagnostic manual, to reflect scientific and medical advances. It hopes this reclassification will “reduce stigmatization” while ensuring “access to necessary health interventions.” 2

On the other hand, while the proliferation of protective lactobacilli in cisgender women can be explained by hormones, the hormonal status of transgender women (comparable to that of cisgender women due to treatment) seemed to make no difference. Further studies on larger numbers of transgender women will be needed to better understand their neovaginal health.

The vaginal microbiota

Microbiota: a well-connected network that influences health

Microbiota: a well-connected network that influences health

Everything you always wanted to know about penile microbiota (but were afraid to ask)

Everything you always wanted to know about penile microbiota (but were afraid to ask)