So we had many, many questions. I will take some. So so the first one is for Florence.

Since you started, do you feel a progress or a backlash towards vagina or female genital topics?

Oh, that's an interesting question. I think through my work in the vagina museum, we've seen a real positive change in the way that people have been talking about the gynecological anatomy, and I can give you lots of examples about how I've changed people's minds and improved people's lives. I think in the wider perspective though, there is an interesting thing happening that the whole world, I feel like, is becoming more and more polarized, and there's data to show this. And of course, women's rights come into that, it's not just politics, but, you know, there's a lot more shame, and you go on the Internet and you see even, like, you know, people are criticizing women if they dress like the way they dress, the way they look and everything. So But on the other hand, then there are a lot of people who are becoming a lot more, supportive. So it's hard to say. In some in some areas, yes. In some areas, no. Okay. Thank you, Florence.

I have one question for Sarah. So you mentioned the Isala sisterhood, the daughter project such as the “Nuna project”? Can you tell us a bit more about it?

Yeah. Definitely. So, another question we just received questions via Instagram and social media, and women were like, yeah. “I'm I'm wearing this type of underwear, and what's the best fabric?” And then we were like, oh, we don't know if there is a best fabric. And we also don't wanna move towards a society where women get the whole list from their gynecologist, like you have to do this and this and this and this, and then they still have an infection because it's maybe just genetics and immune system.

So we started to to set up a study, and then we actually were thinking, it's not just underwear, it's also our menstrual hygiene products. Every month we have, we use them and, and they're they haven't been studied before and they impact on the microbiome. Recently, there was a report about chemicals being found and toxins in the product, but not their impact on our health. But, okay, if they're found, then they must be doing something.

So now we have the Luna project where, they're actually almost finishing the women. So it's a hundred women, those that take the pill and those that don't. And every month they wear another type of menstrual product. So we have the tampon, we have the pads, we have the menstrual cup, and then we have two types of menstrual underwear. So we have the cotton and synthetic, and then they're sending it samples to our lab, so we're analyzing them.

And we're doing actually, similarly in Peru and in Cameroon where women wear the pads and the and the tampon. So, we hope to compare the data. But from the so this is an intervention study from the Isala study that I talked about.

We do already saw that wearing, the menstrual pad was some kind of indicated for a more diverse microbiome. But this this is something that sparked our interest, and we wanted to see if it's necessarily that or it's different or the way people wear it.

So it's it's more than that. It's always better to understand what's the cause, so we're doing it right now. Thank you. Same to Sarah.

A question for Alessandra: How to open women's words during a consultation?

- If you don't have receptors, there is no way. Mhmm. I mean, if we are not trained first Okay. To clinical history.

- Second, to listen carefully to pain as a leading symptom of every consultation.

- Third, if we do not update our knowledge in pathophysiology, what's behind I mean, pain is the tip of the iceberg.

But as a doctor, I must know the pathophysiology that maintain this pain. So if I have not of this, there is no conversation. Not at all. So that's why I'm so critical about the level of training today, because we are all evidence reading papers. Imagine that is a study, a report in US. A resident spend one hour and a half in the ward with patient and the five hours and a half with a computer on the computer. So are we curing papers or are we curing human being? Mhmm.

If we do not change and re put the priority of the body, as I say, as the first protagonist, I don't see a bright future, honestly. So a lot of ideology and a loss in the heart of medicine. A lot of things to change. A lot. Yes, but we are committed. And together, maybe we can change with different perspective, but with one goal, to improve. Thank you so much, Alessandra.

Question for Florence. How could we educate young population regarding specificity of intimate health?

That's a very big question. There there's a lot of ways we can educate young people.

- I think schools is one, but I think sometimes there's too much focus on only schools.

- It also needs to be in the home and parents need to be confident and comfortable to teach their children. We have a lot of people come into the vagina museum saying, you know, I have a toddler and I need to start really teaching them about their bodies. What should I call their parts? I don't know what to say. It feels so inappropriate to just say the words. And I say, no. They may be three years old. Call it a vulva. It's like, it might feel a bit strange to hear a three year old say the word vulva, but it's much better than, you know, fufu and fanny and mini and front bottom and all of these things. Because when you use those euphemisms, what you're saying is that this is a part of the body that should be kept away and you should be ashamed of.

- But then also we need to teach young people in our culture as well, and make it more normalized. For example, in Sweden, there is a really cute cartoon, I can't pronounce Swedish, so bear with me, but it's called Snopon and Snippen, and it's a little cartoon and it's like a little speaking penis and a little speaking vulva to teach young children.

And also, there's a Yeah. Well, so and it Sorry. I I could talk for hours about all the different great educational initiatives. But, the point is that it must be in every single axis of our society, not just in one. Thank you, Florence.

You wanted to add something?

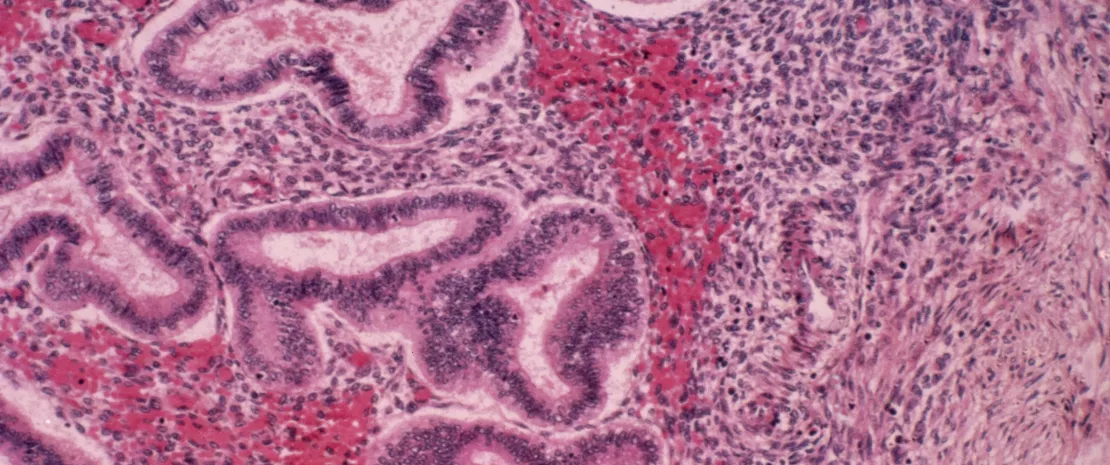

Alessandra: Just to stress that every woman still call vagina the vulva. Mhmm. And they say my vagina is dry, but they mean the vulva. Mhmm. So that's why I was insisting having the picture on the desk of every doctor and say, having the vertical and the or the picture of the vulva. So that we say, where do you have pain? Where do you feel itching? Where do you feel that something is burning? In the map. And also, so in, for example, that the hymen is the line of separation between the real vagina, that is up and the vulva. And this, vestibulum, is the richest in sensitive fibers. So that means a lot of pleasure if everything goes well, but a lot of pain if something goes wrong, and the microbiome has a huge say there. Right.

Even adult women should learn that the vagina is the one the channel up there Yes. And the vulva is the outside. And when they have symptoms, they should use the proper words. So the education is not, fundamentally agree a 100 % for children, but unless the adult use the appropriate language. Otherwise, we are really mismatching even the site of the symptom. And if you are not a very accurate doctor with the picture there saying, what are we talking about, You miss the point. Yeah. So educations about anatomy of women. Exactly.

Sarah, a question for you. How many people are involved in ISALA project as a whole?

Oh. I think in Belgium right now, we have about 10,000. And then worldwide, I don't have the exact number because it's everyday sampling. But, for example, tomorrow they'll be coming samples from Cameroon, and a researcher is coming with them. So, yeah, it's it's growing. So our goal is really to create, like, a global atlas of the vaginal microbiome.

Huge. Very huge. Thank you.

Alessandra: What can be put in place to prevent menstrual pain?

Huge question. Why do women have menstrual pain? Why some have menstrual pain? What are the predictors? We have a huge study from UK on 5500 women with endometriosis and 22000+controls. What we found if what they found.

If women have heavy menstrual bleeding, the probability of having then endometriosis is 5 times the odds than women having normal bleeding.

But, important, if women have heavy menstrual bleeding, they are anemic, iron deficient anemia, and this doubles the risk of depression and doubles the risk of low sex drive. But none sexologists ask about periods and checks if there is anemia. So everybody spend ages with psychologists when you need iron.

Second, if you have pain at intercourse, you have 10 times nine 9.8 the odds of having endometriosis. And if you have pain during periods, 9.8 again. But if you put the three together, the risk is 22.9. This means that Amazing. Obviously, you have something serious. Yes. So what should I do? First, very accurate clinical histories. Check everything, your mono profile, blah blah blah. And then give a progesterone. Give a pill. Give a patch. Give a something to normalize the level of estrogen. Why that? When estrogens fluctuates, they are a trigger of inflammation. When they're stable, they reduce inflammation. This is a major point in infertility. It's still confusing because people don't different people, researchers, physician, don't differentiate fluctuation versus flat.

Remember, 100 years ago and from 200 000 years, women had maximum, as I was saying rapidly, 140-150 periods in their all fertile age. Very often less than 100. Because late puberty, a monarch, then many children, two years' lactation. So early death, by the way. So now we have tripled the menstruation. This means 13 periods per year. And if you have pain, this mean 13 peaks of immunitary fire.

This means if a heavy menstrual bleeding, that the blood goes inside the pelvis, disseminate, and creates endometriosis. So we cannot dismiss heavy menstrual bleeding. 20% of women have it. One in five. Yeah.

So just to give you numbers, because this is the evidence we need, but then go back to pathophysiology and change the destiny. Voila. Very good. Thank you. Thank you, Alessandra.

Now, I have a question for all speakers. We are talking about women's, but, yes, how to get men more involved in women's health?

Florence: Well, I mean, at the Vagina Museum, we some people sometimes ask, can men visit? Of course. I'm like, yes, obviously. And the only people that have ever said, oh, maybe I wouldn't visit are gay men. But even they love it and they come as well because they come with their friends, and they have sisters and mothers. Everyone understands they need to learn about it. We often have single fathers come in with their daughters especially because they think, Oh, I'm going to have to talk about puberty with them, and I don't know how to talk about that because I've never had a period. So maybe the gallery assistant or the person on the front desk can help. So we have a lot of that. But we have men of all different ages, and I think a big part of it is just saying, Yes, you are allowed to talk about this, you are allowed to ask me about this. And some of the ways in my personal life I do that is if I'm going to the toilet because I need to change my pad, rather than hiding it up my sleeve or something, I just take it up and I just walk. You know? And I say, I'm not gonna be ashamed. Are you embarrassed? I'm not embarrassed. Thank you. No problem.

Sarah?

I think it it starts very early in school already. If you talk very openly about the topic, about educating, and everybody if you sometimes even guys have to write, like, a a report on the vagina or the microbiome or whatever, then it it already starts like that. And then it's also exposure. Exposure does a lot. And, yeah, I think it's also up to us women to not just make it be for women by women. No. It's for everyone. It's relevant for everyone. But men also need to educate themselves. They were old enough, it's not just about discrimination or racism, but you need to educate yourself about, yeah, what's everybody knows a woman, even if you don't, then it's still relevant. So, I think it's about responsibility and education, in a way.

But I feel like there is a shift right now. I see even our research team is very diverse, and the guys are very ”I studied the vagina for eight years” already, so it's totally fine. So, it's openly talking about it, I guess.

Alessandra: Well, a number of consideration.

First, imagine in the history, breast was a prominent sign, not the genitals. And today, we have a major problem. You can confirm that Because in anatomy books at school, labia are represented as two tiny lines. And today, we have a huge request of labiaplasty Mhmm. To make the labia thinner and smaller. That is absolutely a mediagenic and “book genic” disaster, first.

On the other hand and in positive, when I have husbands, fathers or sons, accompanying the woman in the medical consultation, I can say that I see the best of the male side of the world. Because I don't like this polarization, we women all the best and the other all the evil. No. Let's say that we are also we do have stupid women and we have smart men. And what is my privilege, having had so many men accompany their partner or daughter, is to see that when I explain to them why she has pain, why she has pain at intercourse, and I explain the biomechanics of pain, the face of the husband or the lover, whatever, changes, Because I'm speaking as a man would like to. Not everything psychological, she's refusing you, she doesn't want to have sex, blah blah blah. But there is a mechanical reason. She's the door is closed. Let's open the door. I can teach you if you want and she wants how to relax the pelvic floor as a foreplay. And they become the best assistant. So let's work together, not polarize all the good and all the evil. No. There are quality people, both gender, and if we collaborate, this is my main message. Otherwise, the fight is a waste of energy.

Florence: Can I Yeah? Oh, sorry. Can I share a really quick story from the Vagina Museum that you reminded me of, where this is one of the best things that's ever happened. In the Vagina Museum, we have a wall of photographs of vulvas of all different shapes, hair, colors, everything. It's really diverse and you can spend hours looking at it. And one of our receptionists told me that one day two women came out of this exhibit and were talking right in front of them, and one of them said: “You know, I think my boyfriend just doesn't appreciate the way my vulva looks.” And having looked at the exhibit, they're like, “Oh, wow, everyone's so beautiful, I'm so beautiful, I'm so unique, and my boyfriend, he doesn't appreciate it.” And then she picked up her phone and she dumped him there and then. No. I was like, “changing lives”.

There's also a question for Sarah: How can we help in the development of ISALA project worldwide?

Oh, of course. You're very welcome to join. You can just follow, the project. We have a newsletter coming out. We'll every, every season where we update about the results, about everything that's going on. But you can also participate. Look if there is an Isala project in your country.

If there isn't one, you can check-in with us and start one. What's the name again for the the French one? Madeleine. Madeleine. So there is also one in France.

So, then if you're in France and you wanna participate, then, I can link you up. It's, it's together with Institut Pasteur. So, so we also have a French sister. So yeah.

And I just wanted to follow-up on the topic of before. I've one of the studies that we do with the sociology, we also noticed that doctors are ashamed to talk with their some of their especially male doctors. And even if it's a woman with a veil or if, if she's more diverse or if they're like, oh, she's for example, we had to study with breast cancer, patients, and they also can have a vaginal dryness, and it can hurt a lot. And even then, they don't. They discuss everything about the treatment with the women, but then if it comes about vaginal health, they're, like, a little bit ashamed. Like, oh, we don't wanna talk about sex with you. Maybe you don't have sex. Like, but everybody has sex. So that's kind of I think it's not just us, it's really all physicians to be able to be also open with your, with the women, and it doesn't depend which color they are. Everybody, has a life and they deserve actually the information. So I just wanted to put it out there that that's also still an issue. And we always think that the doctors tell everything and are not ashamed, but even they feel a little bit of shame.

So Thank you. Thank you so much. Just one minute because we are we are we are very, late. So you you wanted to to say something last word Alessandra:

I have a question for her because it was very interesting on the data you presented. So if I read correctly, you said that the Crispatus was 48%. Mhmm. But I was surprised to find that, Jensenii, Gasseri were 3 and 4%, whilst from the literature, it seems they are much more represented.

So my question is, did you find that this is is this a medium about the data you have? Or is it in Europe? So because it is really different from what we have in our evidence in the books.

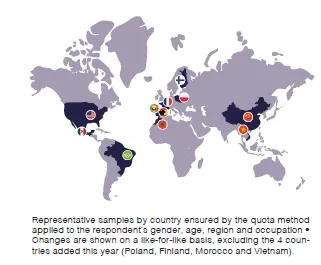

Sarah: Yeah. I think it's it can be very centralized sometimes to countries. But, if you look at The US data, it's it's quite different. But they also kinda, strategize it. It like, stratifies it into race, which is kind of a social construct, and it doesn't make sense to make a distinction. And we have to more look at socioeconomic levels. And I think that's kind of where we're trying to improve is to also have women of all layers of society, women living in poverty, or have different access to preventive care. So that's also a different group to approach.

But I think generally, West Western Europe can be quite similar. Okay. Unless you go deep dive into groups and you have to more look at socioeconomic status. But if you go in the in the world, there is, for example, in Uganda, vaginal soaps are really hot topic. It's being advised everywhere. In the stores, you have all kinds of brands. So that's also, let's say, like, marketing culture. But we're also starting one in Italy, actually. So Good.

So thank you very much. I would like to thank you all of our incredible speakers, Sarah, Laurence, Alessandra. Thank you so much.